In

a now-famous paper, Alan Rogers once

argued that sexual recombination was largely responsible for temporal discounting via kin selection. If people have, on average,

around two kids each of which share half their genes, then at a similar point in their lives, investments in those kids are around

half as valuable to a parent as investments in themselves. In the case of the kids, half of any investment by a parent would go

to a bunch of unrelated genes from somebody else. If a generation is around 25 years (for women) and 30 years (for men).

That results in around 2% temporal discount annually.

Much the same effect likely also resopnsible for the rate of senescence. The future losing half its value in every generation

is not an unreasonable description of senescence. The net effect is that parents are disinclined to invest in their future selves

(as well as their kids) - because they will be old people in the future.

This post is about the effects of cultural, microbial and other symbiosis on this result. Four points:

- Firstly, culture and microbial symbionts are important. In our bodies, microbes outnumber the human cells 10 to one. In some respects, we are more microbe than man. Viruses are ubiquitous too. Cultural symbionts have enabled us to conquer the planet. We outnumber chimpanzees by more than 20,000 - 1. The effects of culture so far have been enormous.

- Secondly, culture and microbes frequently engage in sexual recombination. Microbes inject their genes into passers by and

pick up new genes by eating them. There's also some asexual reproduction going on at the same time. Culture is broadly similar -

many ideas like to have sex.

- Thirdly, culture and microbes often have very short generation times. If the logic of kin selection discounts the future according

to the generation time, short generation times could be resoinsible for large discountung effects.

- Fourthly, the interests of the symbionts matter because they are in a good position to influence their hosts. Microbes live inside

their host's body. If they want more food, they can manufacture hormones that make their hosts hungry. If they want to spread

to others, they can make their hosts cough, sneeze, shit, pee, cry or bleed. Cultural symbionts spend much of their lifecycle inside their

host's brain. They have access to the behavioural master control system. There are immune systems designed to prevent

such access, but these are not completely effective and sometimes fail completely.

What is the effect of all this? Do we discount the future more due to the interests of our symbionts? Alas, it is hard to say exactly, because some of the symbionts are asexual, which invalidates the above argument. Also, while microbes and culture sexually recombine, they typically don't have a fair meiosis that discards half their genes in every generation. Another effect with microbes and with some culture is that there's not much parental investment due to constraints. Microbes can't easily invest in their offspring after they are born. If they get extra resources after that, investing them in existing offspring is not an option.

Since direct theoretical analysis is a bit muddy, can we get a handle on the result we are interested in by proxy - e.g. by looking at how microbes affect lifespan? Faster senescence equates broadly to more future discounting. I think that approach is more promising. Culture fairly clearly reduces the rate of senescence. Highly encultured countries clearly have retarded senescence. With microbes we typically see the reverse result - fewer microbes are associated with longer lives. These results come mostly from cross-country comparisons rather than controlled experiments - so they mostly have the status of associations, rather than causal influences.

Culture looks good today, but theory suggests that it might turn against us if horizontal transfer continues to rise in importance. "Vertically" transmitted culture tends to be aligned with the interests of the hosts. "Horizontally" transmitted culture - not so much. Culture has become increasingly horizontally transmitted over time. Perhaps soon it too will be treating humans as disposable recepticles - shortening our lives in the process.

Looking at effects on lifespan allows us to quantify the effects of microbes and culture on temporal discounting. The effects might have been bigger in the past before microbes and culture could spread internationally so much - but cross-country comparisons show around a 30% variation in life expectancy at birth today. It is probably fair to assume that that is mostly down to microbes and culture - rather than variation in the human genome. Microbes and culture probably do matter - but they are probably not a huge factor.

Update: I should say that the Alan Rogers paper is not really right and senescence explains discounting better than kin selection does. Asexual creatures also discount.

Biologists like to classify selective events. Natural selection, artificial selection, sexual selection, kin selection, group selection and observation selection are all examples of selective categories. This post is about two more categories - self selection, and other selection. These are classification categories which mainly apply to individual decisions.

Biologists like to classify selective events. Natural selection, artificial selection, sexual selection, kin selection, group selection and observation selection are all examples of selective categories. This post is about two more categories - self selection, and other selection. These are classification categories which mainly apply to individual decisions. I recently wrote a summary article about why humans are hairless. The content is broadly similar to my much longer 2011 article on the topic, "

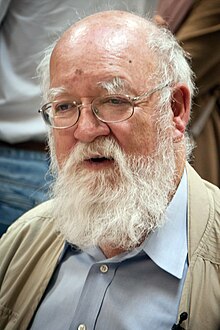

I recently wrote a summary article about why humans are hairless. The content is broadly similar to my much longer 2011 article on the topic, " Here is Dennett,

Here is Dennett,