Jerry Coyne offers a spirited defense of the modern synthesis in his recent article:

Jerry Coyne offers a spirited defense of the modern synthesis in his recent article:

Famous physiologist embarrasses himself by claiming that the modern theory of evolution is in tatters

Unfortunately, Jerry embarrasses himself over the issue of cultural evolution, writing:

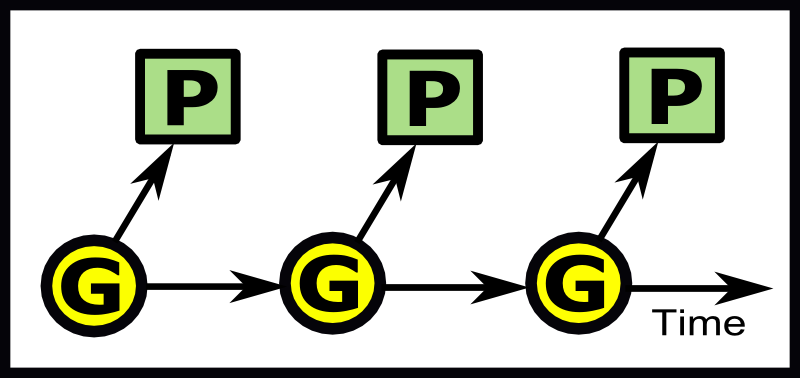

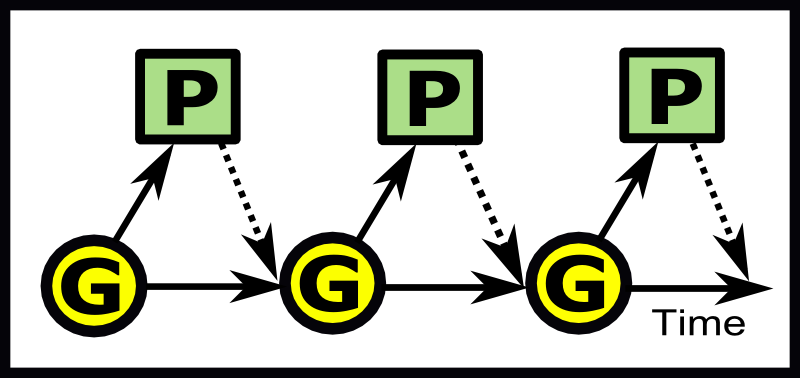

Geneticists now know the genetic basis of dozens of adaptive traits that differ between populations and species. All of them reside in the DNA. If non-genetic adaptive change was common, we would have found it.

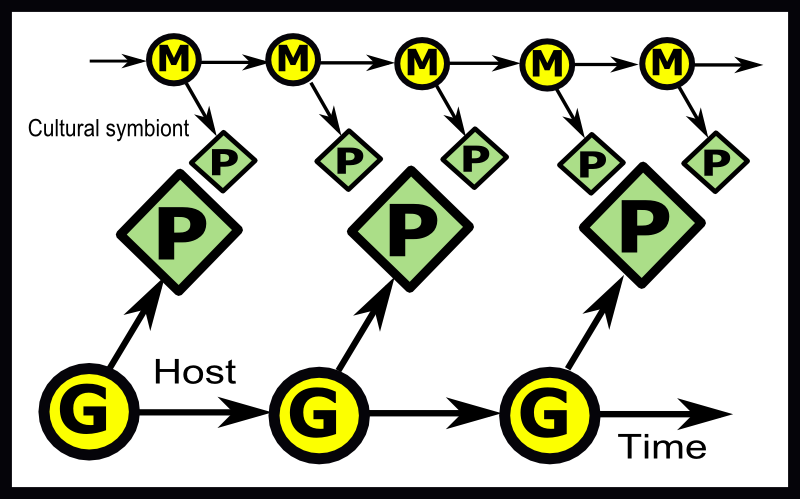

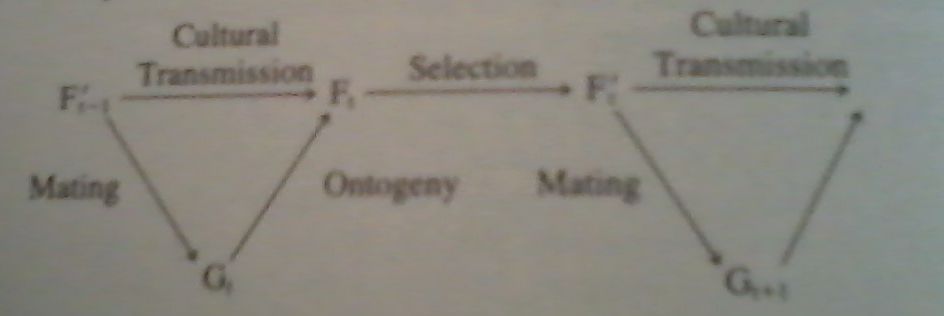

Jerry, we did find it. It's culturally transmitted. Memes let humans inhabit Greenland, live underwater and in space. They let Mormons and Amish have five kids each and led to the modern population explosion. Non-DNA-based adaptive change is very common in human beings - and it is quite common in various other animals that exhibit cultural transmission - from chimpanzees to fruit flies. Jerry appears to be simply unaware of this important discovery - describing it instead as among:

superficial and meaningless parallels with natural selection’s winnowing of genetic variationThe modern synthesis is toast. It is Jerry's attempted defense of it which is an embarrassment. His position is straightforwardly factually mistaken.

A large criticism of memetics was published in 2012:

A large criticism of memetics was published in 2012: One issue concerning the definition of memes is whether their parts are necessarily

One issue concerning the definition of memes is whether their parts are necessarily

Homo Sapiens has been the proposed name for modern humans for a while now. However,

it has become increasingly clear that it's not very appropriate.

Homo Sapiens has been the proposed name for modern humans for a while now. However,

it has become increasingly clear that it's not very appropriate. In the chapter in

In the chapter in

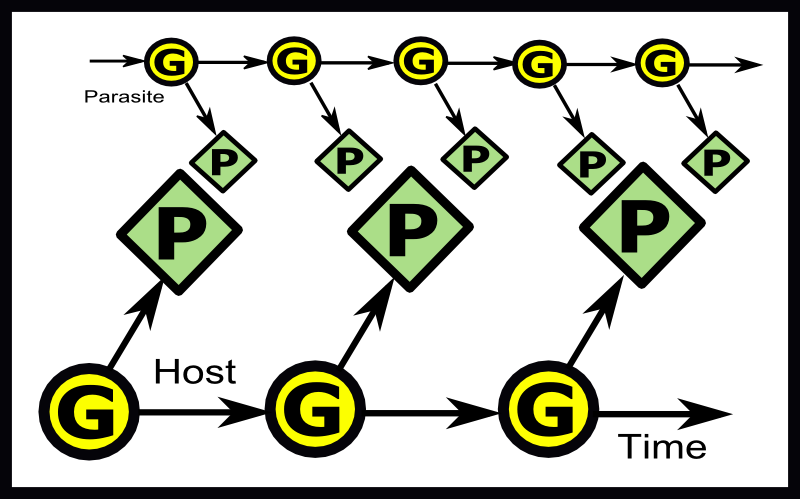

As with many blisters, cities contains swarming organisms that are capable of

spreading the blisters to new areas - in this case, meme-infected humans. Roads act as the main vessels through which the infection is spread. Ships can spread the infection across the oceans.

As with many blisters, cities contains swarming organisms that are capable of

spreading the blisters to new areas - in this case, meme-infected humans. Roads act as the main vessels through which the infection is spread. Ships can spread the infection across the oceans. The invasion of the biosphere by memes has had some rather negative consequences -

as well as some positive ones. In particular, memes are primarily responsible for the ongoing

The invasion of the biosphere by memes has had some rather negative consequences -

as well as some positive ones. In particular, memes are primarily responsible for the ongoing

It seems like a fairly simple and straightforwards prediction of memetics that there will be a

It seems like a fairly simple and straightforwards prediction of memetics that there will be a