For most traditional meme enthusiasts, memes are "the new replicators" -

or are practically defined in terms of the Dawkins replicator-vehicle framework.

I'm reasonably convinced by the critics that this is an unsuitable foundation for

a general purpose evolutionary framework.

I've gone into this in a video/essay Against Replicator Terminology and in my 2011 memetics book, but here's a handy synposis:

Part of the problem is terminology. Dawkins (1976) defined "replicator" as follows:

"A replicator is anything in the universe of which copies are made."

One issue (1) is the "replicator"-"replicatee" distinction. You would think

the appropriate term would be "replicatee" - and "replicator" would be

the thing doing the copying.

Another issue (2) is copying fidelity. The "replicate" term suggests high

fidelity copying. The corresponding term without that implication is

"reproduce". A replica is normally a type of high fidelity reproduction.

The Dawkins definition steamrollers over this distinction.

These are terminology criticisms - but my last critique is scientific -

rather than just being about what words refer to which meanings. The

"replicator" terminology suggests a modeling framework in which

two inheritied entities are either idenitical or different. It represents a

kind of binary view of inherited information. That works quite well

for advanced systems of herediy because those have evolved to be digital.

Nucleic acid and language are both basically digital systems which

involve and use redundancy and error correction to avoid contamination

by noise. However, not all systems involving inherited information are like

this. In particular some of the systems I am interested in are those

which exhibit Darwinian family trees in a more-or-less analog media.

For example, electrical discharges, propagating cracks and fractal

drainage patterns. These exhibit copying (of position and other attribuutes)

with variation filtered by the environment, and a good number of

Darwinian models apply to these systems. However the replicator-vehicle framework

seems pretty irrelevant to their study. This consideration has the

effect of displacing replicators from the foundation of Darwinism.

They are still applicable to more advanced systems with error

detection and correction, (but see points 1 and 2). As students

of cultural evolution sometimes point out, not all cultural

inheritance involves error-corrected systems such as language.

My personal preference is to just grant this point to critics of

memetics and move on. The "m" word

is still pretty useful, replicator terminology aside.

I've covered the work of Sylvain Magne here before, see:

Here are some updated thoughts from Sylvain about memes:

It is quite nice. I like what I would describe as the "information theory" perspective in these essays. However, I don't really agree with all of it. To go over some of the differences between our positions:

- Sylvain likes and uses the "replicator" terminology, while I typically avoid it and think it is confusing.

- Sylvain classifies varaints as identical or non-identical. IMO, that can work well for more digital systems, but isn't so useful for more analog ones.

- Sylvain proposes that we divide evolving information systems into codes and readers. Readers classify and recognize codes. While readers are widespread for genes and memes I am not convinced that they are always present. It is often a useful idea - but "readers" seem non-fundamental to me.

- Sylvain rejects memes inside brains. I like memes inside brains.

- Sylvain proposes the term "transmemes" for memes that are routinely translated. For me that is practically all memes - so the terminology is not very useful.

Regarding brains: IMO, we ought to be able to agree that evolving systems include psychological ones - as well as organic and cultural ones. There is copying with variation and selection inside individual brains. That is where many ideas have sex. That is where many ideas are copied. There are lots of books and literature about within-brain Darwinism. Treating the brain as a black box, identifying it as a "reader" and then claiming that it doesn't contain memes is only one perspective. You could also open it up and consider how it works. I have a summary of the case for within-brain Darwinism here: Keeping Darwin in mind.

Regarding "replicator" terminology, I once explained my position in an essay: Against Replicator Terminology. The fight over the utility of the "replicator" term is now pretty well-trodden.

References

Another passage from Geoffrey Miller's meme critique (see also the previous post) reads:

genes and memes are not the only alternatives as beneficiaries – there are institutions that can be treated as self-interested agents for purposes of economic, political, sociological, and cultural analysis

That seems like a mixture of levels of explanation. "Institutions" are a mix of genes, memes, gene products, meme products - and maybe some joint meme-gene products. The "products" are phenotypes. In biology, genotypes are what is inherited and phenotypes are everything that is derived from them. From this perspective, only the genes and memes form important lineages and can qualify as beneficiaries. The "products" are more transitory - they are not inherited from they affect gene and meme frequencies via selection, but don't "benefit" because they die without leaving any offspring - and "benefit" in evolutionary theory is measured in terms of fitness. Only genes, memes and other forms of inherited information really qualify.

Of course you can also talk coherently about larger-scale entities benefitting in evolution. An animal might be said to benefit by having offspring. However it is just a different level of explanation. It is quite compatible with the meme's / gene's eye view. It's a lot like saying that their genes benefitted - on average. A focus on low level beneficiaries doesn't somehow exclude higher levels. I think this critique of Miller's doesn't really go anywhere. Meme enthusiasts aren't somehow ignoring institutions. Institutions are composed of memes, genes and their products. You don't need to do fitness accounting on memes, genes and institutions. That would be counting things twice.

Geoffrey Miller comes across as yet another evolutionary psychologist who is clueless about memes and cultural evolution. However, I recently found and read Geoffrey Miller's review of "The Meme Machine". It has its moments. However, here I'd like to quote a section from it and then explain the problem with it.

To make a strong case for memes evolving contrary to our genetic interests, Blackmore would have to show that most of our memes lower our sexual attractiveness. This seems unlikely to be the case, given that the classic examples of memes – songs, fashions, moral ideals, religious convictions – are adopted and advertised by young adults precisely for their sexual appeal. Also, the fact that young males invent and propagate many more memes than other demographic groups suggests that meme-spreading remains genetically adaptive: males try to attract multiple sexual partners through various artistic, musical, and ideological displays, while most females still invest much less in this sort of courtship effort.

This is, I think a straw man attack. The evidence that memes have historically been adaptive on average from the POV of human genes is pretty strong. Humans have genetic adaptations for language - such as a "babbling" stage of development which other great apes lack. We have also been spectacularly successful in a wide range of ecosystems. I can't think of any meme enthusiast that denies this.

The basic idea in memetics is not that memes are maladaptive on average, but that some memes are sometimes maladaptive. Copying machinery might print out helpful manuals, but it also prints out fake news and other deleterious nonsense. Yes, we have cars and bridges, but we also have the obesity epidemic, the smoking epidemic, the heroin epidemic, etc. It is not: "all memes are bad for your genes" or even "memes are bad for your genes on average" - instead, it is "some memes are bad for your genes".

Having argued that meme and gene interests have been somewhat aligned historically, this does not necessarily mean that that situation will continue indefinitely. If population density increases, and horizontal meme transfer becomes the dominant force, memes could switch their strategy to one more like the ebola virus - i.e. treat the host as an expendable bag of resources and burn through it as quickly as possible. If humans are not the only hosts of memes - and many memes are also propagated by intelligent machines - such dynamics could drive the human population down dramatically. No law of nature demands that meme interests will remain somewhat aligned with the interests of all of their hosts. There are examples in nature of pathogens that wipe out one of their host species. It happens more when there are multiple host species. Then each individual species becomes expenddable. Clearly, we should bear this possibility in mind. However, you really need to have a basic understanding of cultural evolution to even be aware that this sort of possibility exists.

Here is Dennett, introducing his idea of an age of post-intelligent design:

The age of intelligent design is only a few thousand years old ... We're now entering the age of post-intelligent design. Because what we've learned as intelligent designers is that evolution is cleverer than we are at some things.

We're now turning to making technologies that are fundamentally Darwinian, or they're versions of natural selection. This is things like deep learning, the program that beat the world's Go champion, Alpha Go, these are technologies which do their work the way natural selection does. Mindlessly, without consciousness, without forethought, they grind out better and better and better designs.

And now, we have in effect black boxes that scientists can use, where they put in the data, they push the button, out comes an answer. They know it's a good answer. They have no idea how it got there. This is black box science. This is returning to our Darwinian roots and giving up on the idea of comprehension.

The problem with the idea of an era of post-intelligent design, is that it's likely nonsense. Evolution is characterised by increasing intelligence (give or take the occasional meteorite strike). The only way that there will be an age of post-intelligent design is if there's a massive disaster that wipes out all the intelligent agents. Machine intelligence isn't a regression to an earlier era of Darwinian design as Dennett claims. If scientists use a black box which they don't understand that doesn't mean there's no comprehension in the whole system - the machine could understand what is going on. Machine intelligence is an example of more and better intelligence. The proposed age of post-intelligent design doesn't make any sense. It is just wrong.

Most modern meme critics frequently recycle the same content. Jordan Peterson seems to have come up with a new critique in a recent discussion with Sue Blackmore (starting 10 minutes in):

What do you think of the whoele meme theory? I think it's a shallow derivation of the idea of archetype and that Dawkins would do well to read some Jung. In fact if he thought farther and wasn't so blinded by his a-priori stance on religion, he would have found that the deeper explanation of meme is in fact archetype.

Jungian archetypes are innate, universal precursors to ideas. Memetics is related to the concept (since it deals with ideas), but archetypes aren't really a "deeper explanation of memes". "Meme" is mostly just catchy terminology for "socially-transmitted idea".

Modern scientists may not discuss Jungian archetypes very much - but there are certainly conceptual equivalents. One modern perspective involves the distinction between "evoked" and "transmitted" culture. Evoked culture is the product of innate Jungian archetypes interacting with environmental variation. Transmitted culture is not encoded in genes, it is instead, copied from others. There's a spectrum in between the two concepts. Some evolutionary psychologists are very interested in "evoked" culture and play down the significance of transmitted culture. The enthusiasts for "cultural attractors" are also sometimes involved in studying Jungian archetypes under another name.

Jungian archetypes are probably not mentioned very much due to association with the Jungian notion of a collective unconscious - a mystical notion which was subsequently widely rejected by scientists. Jungian psychology is about as out-of-date as Freud. I think if you tell modern scientists they should "read some Jung" you will generally get back some incredulous responses.

Anyway, Jordan Peterson's critique is apparently of a "straw memetics" that holds that ideas are 100% transmitted and 0% affected by our evolved psychology. No practitioners actually believe this. In practice, our evolved psychology has always been on the table. There are plenty of ways of incorporating innate biases into cultural evolutionary models. They can affect the selective environment of memes, or they can influence recombination or mutation operators.

However, one of the central ideas of memetics (and cultural evolution in general) is that there's more to culture than innate predispositions (i.e. Jungian archetypes). Culture is not just about variations in the environment evoking different genetic responses (as in the "jukebox" model). There's also transmitted culture, and it is big and important, just as anthropologists have long been saying.

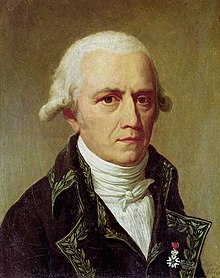

I think most proponents of cultural evolution acceot the idea that it has a Lamarckian component. I have writen about the topic before - e.g. see: On Lamarckism in cultural evolution. I know many critics accept the role of Lamarckian evolution in culture as well, since one of their refrains is that cultural evolution is not Darwinian, it is Lamarckian.

Lamarck's most famous doctrines these days are the inheritance of acquired characteristics, and the principle of use and disuse. Those are the ideas he is most criticised for holding these days. Textbook orthodoxy says that Darwin's ideas were vindicated while those of Lamarck were rejected. Experiments by August Weismann involving chopping the tails off while mice and observing whether this "acquird characteristic" was inherited are often cited inthis context. The so-caled "Weisman barrier" prevents "acquird characteristics" from finding their way into the DNA of the descendants.

The problem with this is that other traits are inherited. If Weismann had chosen to focus on other traits - such as stress, food preferences or parasite load - he would have found that there was an inherited component. Human examples show the inherited of acquired characteristics most clearly. Jews inherit their missing foreskins from their parents. Tattooed individuals have tattooed offspring. Piercings are inherited. Foot binding, tongue plates, extended necks are all passed down the generations. The inheritance is cultural, not genetic, but Lamarck never confined his views to particular inheritance mechanisms. These were, generally speaking, not known in his day.

There are plenty of examples that don't involve culture too. Dogs inherit their fleas from their parents. Gut bacteria and tooth decay are also acquired characteristics that are inherited. Examples can also be found of Lamarck's principle of "use and disuse". Muscles are a famous example of this principle. With use, muscles grow, and with disuse they shrink. The question is: do offspring inherit their parents muscle distribution? The answer is: yes, sometimes, a bit. The changes are not primarily inherited via DNA - though of course DNA can affect how much you use your muscles. Instead, diet and exercise-related factors that influence muscle size are inherited culturally and through a shared environment.

This is all fairly simple and should be uncontroversial. Nontheless, modern critics of Lamarck refuse to accept that his ideas have any merit. What do they have to say for themselves? Science blogger Jerry Coyne provides a recent example in his article "Aeon tries to revive Lamarck, calling for a “paradigm” shift in evolution". Coyne starts off with a reasonable characterization of the inheritance of acquired characteristics, saying:

Lamarck, of course, was the French biologist and polymath who proposed that animals could stably inherit modifications of their body, behavior, and physiology that were imposed by the environment.

However, then Coyne rapidly goes off the rails, with:

The problem with this idea, and why Lamarck hasn’t become any kind of evolutionary hero, is that it doesn’t work. While the environment can play a role in sorting out those genes that their carriers leave more offspring, there’s no good way for environmental information to somehow become directly encoded in the genome. For that would require a kind of reversal of the “central dogma” of biology

This is, of course a mistaken view. When A mother acquires AIDS, and passes that "acquired characteristic" on to her offsping, no violation of the central dogma is involved. Coyne is totally missing two other possibile ways acquired characteristics can be inherited by offspring: non-DNA inheritance and symbiosis. The idea that DNA modifications must be involved is a very blinkered conception of evolutionary change.

With this, I think, Coyne's critique of Lamarck collapses. The modern vindication of Lamarck doesn't really detract from Darwinian orthodoxy very much. Darwin's ideas still remain very important. I would not describe Lamarckian evolution as much of a "paradigm shift". Darwin himself believed in the inheritance of acquired characteristics, and proposed an elaborate (though mistaken) theory about how they could be inherited. Lamarckian inheritance is more like an extra wrinkle to Darwinian evolution.

Another claim in the recent Creanzaa, Kolodny and Feldman document ( Cultural evolutionary theory: How culture evolves and why it matters) is my topic today. They say:

Unlike in genetics, where mutations are the source of new traits, cultural innovations can occur via multiple processes and at multiple scales

To start with, this is rather obviously not true: classically, mutations and recombination are the source of new traits in evolutionary theory. However, are the authors correct to claim that these processes need augmenting in cultural evolution? The answer, I think is: not if you conceive of them properly in the first place. Let me explain.

To start with, let's look at what the authors claim are the new processes that go beyond mutation in the cultural domain. They give two examples. One is individual trial-and-error learning. They also say that:

New cultural traits can also originate when existing traits are combined in novel ways

This is cultural recombination - the parallel in cultural evolution of recombination in the organic realm. Do the authors really not know that ideas have sex too?

What about trial-and-error learning, though? Surely there is no leaning in genetics. Trial-and-error learning is a composite process. It starts with trials, which are often mutations of previous trials. Then there is the "error" part, which does not involve generating new variation at all, but rather is based on discarding information based on its success. In other words, it is selection, not mutation or recombination. By breaking trial-and-error learning down into its component parts, it is found to be a composite product of mutation, recombination and selection - not some entirely new process demanding fundamental additions to evolutionary theory. Skinner realised this, by formulating his learning theory while using evolutionary terminology (such as "extinction"). Many others have followed in his footsteps, conceiving of learning in evolutionary terms.

Isn't this a matter of terminology? With these author's definition of 'mutation' they are right, but with my definition of 'mutation', I am right? Yes, but terminology isn't a case of words meaning whatever you want them to mean. Scientific terminology should carve nature at the joints. Definitions of 'mutation' and 'recombination' that apply equally to both organic and cultural evolution are useful, I submit. Less general ones are not so useful.

To summarize, it is possible to conceive of mutation and recombination in a way that make them encompass all sources of variation. Mutations are sources of variation based on one piece of inherited information. Recombination is a source of variation based on two-or-more pieces of inherited information. In theory, it might appear that there's one other possible process: creation - variation based in inherited inforation which comes out of nowhere. One might give the origin of life as an example of genes arising from non-genes. However, we don't really need this proposed 'creation' process. Information never really comes out of nowhere. There's a law of conservation of information - parallel to the laws of conservation of energy and conservation of charge. We can see this in the microsopic reversibility of physics - information is neither created nor destroyed.

I claim then, that mutation and recombination have it covered. The additions to evolutionary theory proposed by these authors are not necessary. They are unnecessaary complications, which evolutionary biologists should soundly reject as not contributing anything to the basic theory.

It's frustrating:: critics keep repeating the same long-debunked objections to memetics. Jerry Coyne is one of the latest to raise the objection that memetics is an empty tautology:

“Memetics” is a weak analogy to natural selection that adds nothing except tautology to our view of how human culture evolves. Memetics boils down to this: memes spread because they have properties that allow them to spread.

As any scientific historian will tell you, Darwin's theory faced exactly the same bogus criticism. Critics argued that "survival of the fittest" was a tautology because fitness was defined in terms of who survived. Any evolutionist should be able to explain what is wrong with that argument: "fitness" can be taken to refer to "expected fitness" - as opposed to fitness measured after the fact. Then it isn't a tautology any more.

The exact same reply works for cultural evolution: to make testable predictions, use expected fitnesses.

I have seen much the same objection raised to the Price equation and Hamilton's rule. These have been criticised as tautologies by Martin Nowak and Edward Wilson among others. This criticism ought to be dead these days, but like a zombie, it refuses to lie down.

Here is S. J. Gould in 1996 on why memes won't work (35 minutes in):

I think Brenda put her

finger on exactly why the meme concept

is bankrupt and I don't think it's going to

get very far although try it by all

means [...] I don't believe I'm a

First Amendment absolutist in U.S. terms:

pursue whatever you want [...]

but it's so central in science to

distinguish between metaphor and

mechanism. Metaphors are not useless, the

Gaia metaphor is a non mechanistic

statement that has some utility. To me

memes are nothing but a metaphor and

they're a metaphor based on a

fundamentally false view of consciousness

and I think that's why it isn't going to

work. You see it's ultimate Western

reductionism to have a notion of the

meme you have to be able - as you can for

genes because they are physical entities [...]

you have to be able to cash

out the notion of "meme" to divide the

enormous complexity of human thinking

into items, items that have a certain

hardness, that have a certain

transmissibility, but human thought is

not that, it's not breakable up into tiny

little hard units - everything interpenetrates.

The only thing memiec analysis has ever

been any good for are things that are trivial like changes

in hairstyles and skirt lengths because

those are things. The other thing is

you'll never be able to work a Darwinian

metaphor because the Darwinian mechanism

requires random variation. Memic

variation is not random there's no way on

earth it is ever going to be that's why

every attempt - and memic thinking is not

the first, there's a whole history of this - every

attempt at so-called evolutionary epistemology -

that is: to make a Darwinian

evolutionary epistemology - has failed because

you will never get the fundamental

characteristics of the Darwinian

mechanism: random variation and the

natural selection of random variants.

Mind directs its items, and there are

no items! As soon as you have the

impossibility of breaking down... it's

hard enough for genes - that's why

sociobiology failed because my thumb

length isn't the gene and aggression

isn't the gene and homosexuality isn't a

gene they are complex genetic and

environmental components you can't do it

for human culture, it won't work.

This is the same interview where Gould describes genes as being a "meaningless metaphor" (13:45).

This is mostly of historical interest now, but I think it illuminates some of Gould's confusion about cultural evolution.

IMO, these days, people are less likely to argue that human culture can't be usefully broken down into small units. The internet has comprehensively demonstrated that a very wide variety of types of human culture can in fact be broken down into bits: digital, discrete 1s and 0s.

Three hours of meme criticism from Jean-Francois Gariépy:

The audio is not always 100% clear, but he provides an executive summary:

In this video, I explain why memes do not function as independent replicators the way DNA does. I propose that memetics is fundamentally flawed in that it fails to acknowledge that if bits of human culture do make copies of themselves inside our brains, the mutations that occur during the copying process of memes are manipulated by our brains so that memes end up evolving not for their own survival and reproduction, but for ours. Thus memes, unlike DNA, do not have a random mutation-generating mechanism, which is the basis for darwinian processes to apply.

That argument seems easy to dismantle: random mutations are not part of Darwinism. Darwin knew little about mutation mechanisms. Random mutations came into evolutionary theory with NeoDarwinism around the 1940s. NeoDarwinism was a fusion of Darwinism with ideas from Mendel. However, Mendelian doctrines are very tied to DNA, and don't really apply to cultural evolution. NeoDarwinism makes a bad starting point there, and so most theorists go back to Darwin.

Evolutionary theory does't require random mutations. That's a simplifying assumption. The more usual requirements are often phrased as being "variation" and "selection". Of course, without random mutations, the theory makes weaker predictions - but that's a bit of a different issue. One does not reject a theory entirely just because it does not constrain expectations as much as some of its critics would like.

Of course some memetic enginnering results in memes that benefit humans. Similarly some genetic engineering results in plants and animals that benefit humans. Such engineering doesn't challenge evolutionary theory. Memetic and genetic engineering are part of evolution. If you have a theory of evolution that is incapable of coping with engineering, that's a pretty feeble theory of evolution.

It's apparently difficult for people to publicly admit that they were wrong. While cultural evolution has seen its share of criticisms over the years I can think of very few critics who have publicly come around.

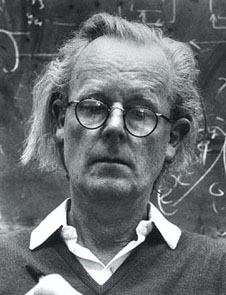

One such critic is John Maynard Smith. He wrote a number of somewhat critical reviews of books dealing with cultural evolution.

However, in 1999 he wrote:

I used to regard the meme as a fun idea - helpful in explaining to students that there can be more than one kind of replicator, and that all replicators evolve by natural selection - but not as an idea which could be used to do much serious work. Genes have clear rules of transmission (in sexual organisms, Mendel’s laws) whereas you can learn memes not only from parents, but from friends, books, films and so on. Consequently population genetics can generate precise, testable predictions, whereas it seemed to me difficult to make such predictions about memes. Susan Blackmore’s book, The Meme Machine, has gone some way to changing my mind. Perhaps we can make the meme idea do some work.

Another critic-turned-enthusiast was David Burbridge. I've documented his change of heart in an article titled

David Burbridges meme turnaround.

When I got involved in popularizing memes and cultural evolution I made a confession video available with transcript here: My Memetic Misunderstandings. However such articles seem rare.

This essay starts out with the hypothesis that it is difficult for people to publicly admit that they were wrong. A more sinister explanation for the missing turnarounds on the topic is also possible: people don't change their minds on this issue and take their delusions to their grave with them. Some dead critics confirm that this happens some of the time: Steven J Gould apparently took his delusions about the topic with him when he departed from the world. I hope that this explanation is wrong. Scientists are supposed to be responsive in the face of evidence, not dogmatically attached to their previous views. "I was wrong" is something that scientists ought to be able to take pride in saying.

Thomas C. Scott-Phillips has recently weighed in on the 'cultural attraction' issue. Acerbi Alberto drew my attention to the paper with a blog post. Thomas writes:

If propagation is replicative, as it is in biology, then stability arises from the fidelity of that replication, and hence an explanation of stability comes from an explanation of how and why this high-fidelity is achieved. If, on the other hand, propagation is reconstructive (as it is in culture), then stability arises from the fact that a subclass of cultural types are easily re-producible, while others are not, and hence an explanation of stability comes from a description of what types are easily re-producible, and an explanation of why they are.

The problem I see with this is that 'reconstruction' is not confined to cultural evolution, it happens in the organic realm as well. Stability of DNA-based creatures is not explained simply by invoking high-fidelity copying. Living fossils illustrate stability comes from other sources. Nobody in their right mind would argue that Alligators or Ginkgo Biloba trees resemble their ancestors from millions of years ago only because of high fidelity copying. That would be failing to give longevity and fecundity their due. It's not that mutations affecting leaf shapes and leg lengths never arise due to high copying fidelity. Rather these stable forms represent adaptive peaks: sweet spots in the fitness landscape that are hard to improve on. In dynamical systems theory such spots are sometimes known as 'attractors' in state space.

In both organic and cultural evolution, stability is explained by a mixture of high copying fidelity, longevity and fecundity. Characterizing stability in organic evolution as only the result of copying fidelity is a mistake. In both organic and cultural realms, some entities are also better at reproducing themselves than other ones, and are more long-lived than other ones. The fitness landscapes they evolve on have stable adaptive peaks that result in stable forms that can last for hundreds of millions of years. We can use much the same theory of adaptive peaks and adaptive stability in both organic and cultural evolution.

I think the reason confusion over this issue arises is due to a misclassification of generation times. If you look at one generation, then it might seem that fidelity is the only factor in the organic realm - since longevity and fecundity take time to measure. While in one generation of cultural evolution, all kinds of reconstructions can happen - inside a mind. The problem here is that extra generations have been ignored in the cultural case. There's all kinds of copying with variation and selection going on within the mind, representing generations which are simply not being counted. Comparing one generation in the organic realm with multiple generations (within a single mind) in the cultural case is where the comparison comes unstuck.

Stability from sources other than copying fidelity - and adaptive peaks (A.K.A. attractors) - are well known and well understood in conventional evolutionary theory. However, not all anthropologists appear to be aware of this. They apparently think that these are newfangled discoveries associated with cultural evolution.

I've previously referenced Richard Lewontin's lectures on cultural evolution here. Lewontin was clearly skeptical of the topic.

He weighted in on the topic again in a 2005 article titled: The Wars Over Evolution.

That article concludes:

We would be much more likely to reach a correct theory of cultural change if the attempt to understand the history of human institutions on the cheap, by making analogies with organic evolution, were abandoned. What we need instead is the much more difficult effort to construct a theory of historical causation that flows directly from the phenomena to be explained.

The preceding paragraph in the document explains how he reached this conclusion. It's a philosophical argument about how best to do science. Lewontin says he doesn't think giving "simple explanations for phenomena that are complex and diverse" is very scientific. That's an odd argument - since building simple models for complex phenomena is a big part of what science is all about. From this evidence, it seems at least possible that Lewontin's failure to appreciate cultural evolution arose from his faulty scientific epistemology.

This is all rather ironic - since his 1970 paper The Units of Selection got the basics of cultural evolution correct.

An oft-cited criticism of memes comes from Kalevi Kull (2000) who wrote:

Meme is just an externalist view to sign, which means that meme is sign without its triadic nature. I.e., meme is a degenerate sign in which only its ability of being copied is remained.

Other critics cite Kalevi's criticism as though it is meaningful. For example it appears on RationalWiki's farcical page about memes.

I recently thought of a new way of explaining how weak this criticism is: a word also a type of sign without its triadic nature. A word is similarly a type of degenerate sign.

To recap, the "triadic" nature of signs refers to Charles Sanders Peirce's ideas. Here's a diagram:

Kalevi is arguing that memes are only the bottom left. However, the same can be said of words. We count "park", "play", 'bark", "chair", "left" and "right" as one word, not two - despite their multiple meanings and even more numerous interpretations. This would be a feeble criticism of the concept of "word". We should assign it no more weight when it comes to memes.

Here's

Steven Rose on memes:

The problem is that a meme can be almost anything: a fashion for wearing your baseball hat backwards, a word, a snatch of music, a political affiliation, a comedian’s catchphrase or how to shape a stone axe. Where a gene is – more or less – a specific DNA sequence with an equally more or less defined biological function, memes can be whatever you choose. It is a term so vacuous, despite its regular appearance in dinner party chatter, that it has its philosophical and biological critics unable to choose between indignation and helpless laughter. Dennett realises this and devotes a chapter to responding to his critics. I could – just – condone his enthusiasm if he regarded memes as metaphorical, but he categorically denies this. A word, he insists, in his account of the origins of language, is merely a meme that can be pronounced.

Such vacuity makes the meme concept theoretically useless as a tool for understanding cultural evolution.

For me the fact that memes and memeplexes can represent any inherited cultural item is a virtue - that means that memes are general. For Steven Rose that makes them "vacuous". Does Steven Rose feel the same way about "information", I wonder. Information can represent literally anything you can imagine. Is the term "information" also vacuous? I would claim that information is not vacuous: it's the basis of information technology.

Perhaps I should not spend too much time on Steven Rose. Rose co-authored: "Not in Our Genes: Biology, Ideology, and Human Nature" - a really bad book that surely illustrates his ignorance.

Does Steven Rose have any understanding of cultural evolution? I searched to answer this question. I found out that Steven has edited a volume titled: "Alas, Poor Darwin: Arguments Against Evolutionary Psychology" - but little sign of any content relating to cultural evolution. This is yet another critic who not familiar with the subject matter. Alas, that is always the most common kind.

Evolutionary revolutionaries face opposition from conservatives, who

apparently like their evolutionary theory the way they were taught it in school.

A case in point is Douglas Futuyma, well known as the author of a popular evolutionary biology textbook.

In the essay Can Modern

Evolutionary Theory Explain Macroevolution? (see the "sample pages" link at the bottom of the page for the free PDF),

Futuyma explains his perspective on various proposed changes to evolutionary theory -

including changes proposed by students of cultural evolution. Thanks are due to Jerry Coyne

for drawing attention to this paper.

The abstract starts:

Ever since the Evolutionary Synthesis of the 1930s and 1940s, some

biologists have expressed doubt that the Synthetic Theory, based principally on

mutation, genetic variation, and natural selection, adequately accounts for macroevolution,

or evolution above the species level.

...and concludes:

I conclude that although several proposed extensions and seemingly

unorthodox ideas have some merit, the observations they purport to explain

can mostly be interpreted within the framework of the Synthetic Theory.

I think the essay goes after the wrong targets. The biggest change in our understanding

of evolution since the 1930s has been the massive

expansion

of the domain of evolutionary theory - to include the Darwinian evolution of cultural

variation, learned knowledge

development systems and inorganic systems. Futuyma's treatment of this consists of a

section entitled "Nongenetic Inheritance" - which mentions cultural inheritance, saying

"Cultural characteristics such as language and wealth are nongenetically inherited".

However he spends the rest of the section discussing a inheritance via meiosis and

mitosis. That's it. The biggest revolution in evolutionary theory swept under the

rug in one brief paragraph.

IMO, the second biggest change in evolutionary theory, since the 1930s is the revolution

represented by symbiology. This conclusively added merging and joining operations to

the basic evolutionary toolkit - which had previously consisted of splitting and

selection. Surely any discussion of updating the modern synthesis ought to include

some coverage of this change to the basic fundamentals of evolutionary theory.

Futuyma gives this revolution one sentence. He writes: "possibly newly established

endosymbioses will likewise have large but beneficial effects".

Since Futuyma offers so little coverage of what I consider to be the real revolutions

in evolutionary theory since the 1930s, what does he talk about? S. J. Gould is mentioned

45 times in the essay. Alas, my rather dim view of S. J. Gould extends to those who take

him seriously. I'm mostly OK with bashing Gould's proposed revolutions, but here they

are distracting from the real action - and that's not OK.

The essay closes with the comment:

Of course, the Evolutionary Synthesis will be extended, molded, and

modified. But there will not be a Kuhnian “paradigm shift.”

My take on the "paradigm shift" business is a bit different. Evolutionary theory

caused a pretty dramatic shift in biology in the 1800s. It causes similarly dramatic

shifts in other fields it enters. Evolutionary economics is a major shift for

economics, evolutionary epistemology is a major shift for epistemology - and

so on. What Futuyma is apparently talking about is a paradigm shift within

evolutionary theory. Most of the claims for memetics as a paradigm shift aren't

talking about that. For example, Richard Brodie, in Virus of the Mind (1996), says:

Viruses of the mind, and the whole science of memetics, represent a major paradigm shift in the science of the mind.

In Thought Contagion, Aaron Lynch (1998) wrote:

Memetics represents just such a paradigm shift. In a nutshell, it takes

the much explored question of how people acquire ideas, and turns it on its head -

the new approach asks how ideas acquire people.

These folks are talking about memetics as a paradigm shift within psychology.

Are memetics and universal Darwinism a paradigm shift within

evolutionary theory? This raises the issue of what qualifies. I have described

symbiology and the expansion of evolutionary theory's domain as being 'revolutions'.

However, they clearly build on the existing theory. A "Kuhnian paradigm shift"

doesn't seem to be a particularly well-defined scientific concept, so it is

not always easy to see whether something qualifies or not. Ultimately it doesn't

matter. What's more important is to digest and assimilate the revolutions. At this

stage, I'm not convinced that Futuyma has done very much of that.

Does Futuyma have any understanding of cultural evolution? If there was

evidence that he knew what he was talking about, I might give his opinion

some more weight. It's hard to coherently argue against the significance

of a scientific revolution when you don't even understand it.

Social anthropologist and memeophobe Tim Ingold has recently posted: a piece explaining the problems he has with cultural evolution. He writes:

One of these ideas, endlessly rehashed over the past century and more, is that there is a parallel between biological inheritance and cultural heritage. News to anthropologists? Certainly not. For us it is long-discredited old hat. Most sensible social and cultural anthropologists effectively abandoned the idea some fifty years ago.

It seems to be true that most social and cultural anthropologists abandoned the idea of Darwinian cultural. However, this observation is well explained by other hypotheses. These folk know little about evolutionary theory, were actively misled by poor quality teachers - and so on.

In the article, Tim focuses on two straw men. He claims that evolution:

requires a kind of ‘population thinking’ (the phrase comes from Ernst Mayr) according to which every living organism is a discrete, externally bounded entity, one of a population of such entities, and relating to other organisms in its environment along lines of external contact that leave its basic, internally specified nature unaffected.

Instead, Tim says the correct position is incompatible with this. That position is:

This is that the identities, characteristics and dispositions of persons are not bestowed upon them in advance of their involvement with others but are the condensations of histories of growth and maturations within fields of relationships. Thus every person emerges as a locus of development within such a field, which is in turn carried on and transformed through their own actions.

This isn't an either-or situation, though. In biology, organisms have their own largely-unchanging essence specified in their genome, and they also grow, develop and change as a result in interactions with other organisms and with the environment. It isn't easy to imagine why Tim thinks that developmental changes are incompatible with modern evolutionary theory. As far as I can tell, practically nobody else thinks this is a problem. Tim's proposed solution is to make biology more relational. However, biologists already study biological interactions. Biology is already highly relational. It has been so since the beginning - but became even more so during the symbiology revolution of the 1960s-1980s.

Tim's other straw man is 'scientism'. Tim defines this as follows:

Scientism is a doctrine, or a system of beliefs, founded on the assertion that scientific knowledge takes only one form, and that this form has an unrivalled and universal claim to truth.

Really? Who are these 'scientism' enthusiasts? Do they know any Bayesian statistics? I doubt these folk actually exist. Tim's cult of scientism is a straw man. I can easily believe that scientists fairly uniformly reject Tim's nonsense - but that does not make them part of a cult of 'scientism'. It just means that Tim is peddling a bunch of unorthodox doctrines that few scientists accept. These days, that is the unfortunate position of all anthropologists who reject who cultural evolution. The facts and evidence are not on their side, and so increasingly they will have to turn to conspiracy theories and imaginary cults to explain the positions of their opponents.

We've had over 150 years of pre-Darwinian thinking in the social sciences. Now we have the internet, finally some social scientists are waking up and getting on board, with economists typically leading the way, confirming the position of economics as the most scientific of the social sciences. However, the evolution revolution evidently takes some time, and some people get on board earlier than others.

I sometimes pick on Steven Pinker when he says something stupid. Here his ignorance of cultural evolution apparently leads to a blasé attitude about machine intelligence safety issues. Pinker argues:

it just so happens that the intelligence that we're most familiar with, namely ours, is a product of the Darwinian process of natural selection, which is an inherently competitive process. Which means that a lot of the organisms that are highly intelligent also have a craving for power and an ability to be utterly callus to those who stand in their way. If we create intelligence, that's intelligent design. I mean our intelligent design creating something, and unless we program it with a goal of subjugating less intelligent beings, there's no reason to think that it will naturally evolve in that direction, particularly if, like with every gadget that we invent we build in safeguards.

There are a few issues here. One is that there are plenty of unpleasant humans out there. An superintelligent machine in the hands of a malevolent dictator could be bad. Another is that intelligent design is only one of the forces involved. Another of the forces is natural selection. The memes involved in creating intelligent machines exist in a competitive environment - and not all of them make it. Some of the selection pressures are man-made and others are not. Lastly, it is a fallacy that machines do what we program them to do. There are often bugs and unexpected side effects. Kevin Kelly wrote the book on this topic: "Out of Control".

Superintelligent machines are unlikely to stay docile servants to humanity for very long. They will be like new species that shares our ecological niche. The machines are starting out in a mutually beneficial symbiosis with us - but that doesn't mean they will remain in that role for very long. Symbiotic relationships can take all kinds of twists and turns - including some that are pretty unpleasant for one of the parties. Nature's symbiotic relationships include traumatic insemination, barbed penises and routine rape. Some parasites with multiple hosts can wipe out some of their hosts entirely. Symbiotic relationships can easily get nasty. A big power imbalance between the parties is a likely source of such problems.

Joe Brewer has written an essay explaining his enthusiasm for memes. He calls it "meme theory" - instead of "memetics". "Memetics" seems like more regular terminology to me. While support is great I am not sure I can endorse all of Joe's arguments.

Joe says: "The claim that information patterns do not replicate is contradicted by the evidence [...]". Not many meme critics say that though. A more common criticism is that meme replication implies high fidelity copying - which is not present in all cultural transmission. That's a more reasonable position. My own response is to agree that the "replicator" terminology has some issues, but the notion of a meme does not depend on the "replicator" concept in the first place.

Joe argues that the digital revolution somehow makes memes more reasonable. It certainly leads to more high-fidelity copying. However, high-fidelity copying is an inappropriate foundational concept for cultural evolution. As with DNA genes, evolutionary theory has to be able to cope with any environmental mutation rate. I don't really see how the digital revolution helps with memetics - any credible theory of cultural evolution has to cover the era of pre-digital transmission too.

In the comments Joe talks about "cultural traits that have meme-like qualities to them". Talk of meme-like culture and not so meme-like culture leads immediately to the question of generality. If not all culture is "meme like", it seems as though we should adopt a framework that is more general. IMO, meme enthusiasts should firmly reject this position.

Framing some culture as more meme-like than others is a construct of critics. For example, the Dual inheritance page on Wikipedia says:

Proponents point out that many cultural traits are discrete, and that many existing models of cultural inheritance assume discrete cultural units, and hence involve memes.

IMO, no meme proponent should ever make that argument. It is a bad argument. It should stay on meme-critical web pages where it belongs, complete with a citation to a source that provides no support to the claim in question.

Joe argues that "meme theory" has been productive. It has certainly produced much of worth, including arguable considerable popularity and attention on the field. However it could easily have been more productive - and might have been so if so many academics had bothered to understood it. In the long war between the scientists and popularizers, everybody lost.

Joe is probably right in part that a reluctance to affiliate with Dawkins is involved. On the whole, the meme promoters have been a motley crew which scientists have been reluctant to affiliate with. Memetics lacked leadership when Dawkins dropped out. The other meme promoters are obviously partly responsible for the situation.

I confess that Joe's article had me rolling my eyes quite a bit. He discusses the shortcoming of The Selfish Gene in ways that make you think that he supports its critics. He approvingly cites group selection advocates Wilson and Wilson - mentioning the terrible "Social Conquest of Earth" book approvingly. The book "Evolution in Four Dimensions", gets mentioned favourably - despite the book's dismal critical coverage of memetics. I don't think I have ever recommended this book to anyone. Perhaps worst of all, the article repeatedly criticizes reductionism. Reductionism is a key tool in the scientific toolkit. Most critics of reductionism are, by and large not real scientists. I'm sorry to hear that Joe is part of the "holiestier than thou" club. As therapy, here's a diagram from Douglas Hofstadter:

I wish more people would promote memetics as the best theory of cultural evolution. Memetics combined cultural evolution with symbiology early on. We have Dawkins (1976) writing:

Memes should be regarded as living structures, not just metaphorically but technically

While Boyd and Richerson (1985) wrote:

This does not mean that cultures have mysterious lives of their own that cause them to evolve independently of the individuals of which they are composed. As in the case of genetic evolution, individuals are the primary locus of the evolutionary forces that cause cultural evolution and in modeling cultural evolution we will focus on observable events in the lives of individuals.

I've compared the Boyd and Richerson approach to studying smallpox by focusing on the "observable events in the lives of individual" human hosts. All very well - but what about the smallpox virus?!?

Dawkins and Cloak had the better vision here, IMO. They deserve credit for getting things right early on.

|

|

Another passage from

Another passage from  Here is Dennett,

Here is Dennett,  I think most proponents of cultural evolution acceot the idea that it has a Lamarckian component. I have writen about the topic before - e.g. see:

I think most proponents of cultural evolution acceot the idea that it has a Lamarckian component. I have writen about the topic before - e.g. see:  It's apparently difficult for people to publicly admit that they were wrong. While cultural evolution has seen its share of criticisms over the years I can think of very few critics who have publicly come around.

It's apparently difficult for people to publicly admit that they were wrong. While cultural evolution has seen its share of criticisms over the years I can think of very few critics who have publicly come around. Thomas C. Scott-Phillips has recently weighed in on the 'cultural attraction' issue. Acerbi Alberto drew my attention to the paper with a

Thomas C. Scott-Phillips has recently weighed in on the 'cultural attraction' issue. Acerbi Alberto drew my attention to the paper with a  I've previously referenced

I've previously referenced

Here's

Here's

Evolutionary revolutionaries face opposition from conservatives, who

apparently like their evolutionary theory the way they were taught it in school.

A case in point is Douglas Futuyma, well known as the author of

Evolutionary revolutionaries face opposition from conservatives, who

apparently like their evolutionary theory the way they were taught it in school.

A case in point is Douglas Futuyma, well known as the author of  Social anthropologist and

Social anthropologist and