The realm of technology is full of systems that cooperate with one another. Printers, cameras and monitors all cooperate with computers. Computers cooperate with networking systems which cooperate with all manner of other devices. How are we to explain this sort of cooperation?

There are two kinds of answer to this question:

- These machines were designed by humans to benefit humans, and they cooperate because this serves humans;

- The machines share memes with each other, so Hamilton's logic of kin selection predicts that they will cooperate;

The first explanation is fairly obvious and makes sense. It is the kind of explanation that evolutionary psychologists might give. The second explanation invokes cultural kin selection. It invokes the meme's eye view and is in the sprirt of memetics. It is one of the ideas I discussed in my 2012 " Cultural kin selection" article.

The idea that artifacts that cooperate to the extent that they share memes has considerable merit. There's

certainly a correlation: 100% shared memes often results incomplete cooperation - while 0% shared memes generally

results in fairly minimal cooperation which is explicable in terms of reciprocity and byproduct mutualism.

As an example of how the process works, let's look at the cooperation that takes place between a printer and a computer when they print a document together. Without that cooperation, no documents would be produced - and the consumer would be frustrated. This could potentially damage the memes in the devices themselves - for example, maybe the printer will be thrown in the trash if it was identified as the defective component. However, the memes in the printer were terribly unlikely to reproduce directly in the first place. The main way they can influence their own propagation is via copies of themselves in the headquarters of their manufacturer. Part of the consumer's frustration will probably be directed towards the manufacturer. This might affect future purchases by the consumer involved. The consumer might mention the problem to other prospective customers. For example, they might write a negative review or tell the story to others. The cooperation between the computer and the printer happens because of benefit to copies of the memes involved at the headquarters of their manufacturer involved.

This example shouldn't be taken to imply that the effect is confined to computer peripherals, a wide range of cooperating artifacts exhibit cooperation which is based on cultural kin selection.

There are some cases where shared memes in some sub-component or interface seems to be more important than overall shared memes. However, if you view single artifacts as symbiotic conglomerates with components from many sources, this still makes a lot of sense - and a kin-selection based approach is still highly appropriate. There also be cases where shared memes in the associated manufactures (rather than the device itself) seems to be a factor. Consumers certainly use the manufacturer as a clue to compatibility - for example with printer cartridges. However, this is just a proxy for shared memes in the artifacts. If looking to the identity of the manufacturer is helpful, that could be a complication when applying the approach.

Technological kin selection has gradually moved from being a minor factor in explaining cooperation on the planet to being a pretty significant one. As we move towards the memetic takeover, technological kin selection seems likely to continue to increase in significance.

The general trend in brain size among our immediate ancestors over the last three million years has been upwards, as this graph illustrates:

However, recently, there are some signs that this trend has abated. In particular Neanderthals had larger brains than modern humans.

Is this consistent with the idea that big brains are meme nests? Surely memes have been on the up-and-up - while brain size has not.

The modern brain shrinkage corresponds to the rise of modern agriculture and increased population densities. Here's a quote from a 2010 article on the topic:

Bailey and Geary found population density did indeed track closely with brain size, but in a surprising way. When population numbers were low, as was the case for most of our evolution, the cranium kept getting bigger. But as population went from sparse to dense in a given area, cranial size declined, highlighted by a sudden 3 to 4 percent drop in EQ starting around 15,000 to 10,000 years ago. “We saw that trend in Europe, China, Africa, Malaysia—everywhere we looked,” Geary says.

Through most of human history the meme pool had to fit in a single brain. There wasn't much in the way of specialization - all the tribe members played similar roles (except perhaps for the doctor). There was probably some gender-based specialization, but that was about it - the meme pool mostly had to fit in a single mind.

With the advent of agriculture, large populations and exchange and specialization - and more advanced language - all this radically changed. Memes were liberated from the confines of a single mind, and the meme pool was able to expand enormously. Towns could support far more memes that any hunter-gatherer tribe could manage. The process of meme liberation eventually led to writing - another major move to liberate memes from the human skull.

The meme pool not being effectively confined to a single mind would have massively reduced the selection pressure on minds to grow to accommodate more memes. Now minds only had to accommodate the memes associated with a given specialization.

Other theories may have something going for them too. Modern humans have been domesticated by their institutions - and domestication often

results in smaller brains - since the domesticated creatures have their defensive and foraging needs supplied for them. Also agriculture led to poorer diet - and that might have had a negative effect on brain size too (though re-feeding modern humans doesn't give them much bigger brains).

However, the idea of big brains as meme nests is at least consistent with the modern cerebral downturn. The modern cranial shrinkage corresponds to the liberation of the meme pool from the mind of a single hunter-gatherer mind. The division of labor that came with large populations would have meant that each specialization had its own, much smaller and largely-independent meme pool. The pressure on the brain to grow to accommodate the entire meme pool of the human race was off - and stupider humans could thrive.

The liberation of memes led to a removal of the size limit on cumulative cultural evolution. Now that they were no longer effectively confined to a single mind, the modern meme explosion began to gather speed.

References

Walking was part of our lineage from the point where it split from chimpanzees - as far as archaeologists can tell.

The idea that walking made us human probably seems naive these days. However,

tools, fire and language followed much much later - and the significance of walking

gets quite a shot in the arm from memetics.

As I explain in considerable detail in my 2011 memetics book, walking was one of the earliest

socially transmitted traits in our ancestors. The need to walk put pressure on infants to

master the social skills needed to learn to walk from their parents and caregivers.

Chimpanzees socially transmit use of tools such as hammers. However, there's nothing

similar to walking in demanding early learning and so profoundly affecting development.

It was walking that kicked the race to develop social learning into a high gear in infants among our early ancestors.

There was cultural transmission before walking - but is wasn't so profoundly life-changing. It is true that the expansion of the human cranium corresponding to colonization by memes didn't begin for another three million years - but that seems consistent with walking having a high significance in the development of social learning. Walking generated pressure for social learning skills to develop early. It was a while before this started having knock on effects that led to an expansion of the skull-bound meme pool - as the size limit on cumulative cultural evolution in our ancestors gradually began to rise.

References

Once serious interest in the topic of cultural evolution was rekindled in the

1970s, something very strange happened to it in academia. Most of the interested

parties became obsessed with the topic of meme-gene co-evolution. Retrospectively,

this seems like a curious approach to exploring the subject area. I have likened it

to trying to fly before you can walk. The more obvious approach is to study cultural

evolution first - and then go on to study the more advanced, esoteric and difficult

topic of meme-gene co-evolution later.

The work I am mostly talking about resulted in four books. These ones:

- Lumsden, C. and Wilson, Edward O. (1981) Genes, Mind, and Culture.

- Cavalli-Sforza, L. L. & Feldman, M. W. (1981) Cultural transmission and evolution: A quantitative approach.

- Richerson, Peter J. and Boyd, Robert (1985) Culture and the evolutionary process.

- Durham, William H. (1991) Coevolution: Genes, Culture, and Human Diversity.

These books don't really represent a sample of the field, these were the first books

on the topic and were pretty-much all of the books on the topic at the time.

In this article, I will argue that this focus on the distant past was unhealthy one,

and has produced a hangover that continues to this day.

The problems with focusing on meme-gene co-evolution are that:

- The topic is difficult and demands a deep understanding of cultural evolution;

- The distant past, is a difficult area to explore.

The problems with studying the distant past are that:

- Evidence is difficult to obtain;

- Experiments are challenging to perform;

- Predictions are difficult to test.

As a double-whammy, researchers in the field appeared to all be copying each other. There was a cultural founder-effect

and the focus on meme-gene coevolution spread to most of the researchers involved.

Why this happened in the first place is not entirely clear. Some of the researchers

involved were heavily interested in genes and genetics. For Lumsden, Wilson, Cavalli-Sforza

and Feldman, the idea of a meme must have been immediately followed in their minds by

questions about how this related to all the things they already knew about genes and

DNA-based evolution. These were researchers who were already obsessed with ancient human

history long before they developed an interest in cultural evolution. Another issue

may have involved funding sources. Research would often have had to be framed in terms

that administrators could understand. A fringe research area that fell between academic

departments and had no established community needs to get funding somehow - and

perhaps the link to human DNA-based evolution helped with funding the field. Another

possibility is that if other folk in your field are studying a difficult and esoteric

topic, you have to join in to keep up. Going for meme-gene co-evolution suggests that

you already have the topic of meme-based evolution down pat - and are ready for more

advanced topics. This could have been a case of academics deliberately focusing on

complex and difficult topics - for the sake of prestige.

Whatever the reasons, the early history of cultural evolution in academia

largely turned into the history of meme-gene coevolution.

If instead the focus had been on memetic evolution, probably a lot more progress

could have been made. To a first approximation, genes represent a static background

against which cultural evolution takes place. This is because cultural evolution

has such short generation times and takes place so much faster than the evolution

of DNA-based human genes. This means that you can usefully study cultural evolution

while ignoring the complex and difficult topic of meme-gene co-evolution.

Cultural evolution is highly visible in modern times. There is an enormous wealth of data,

and experiments in the field are simple and easy to perform. Furthermore, there

are big practical applications on hand. Advertising and marketing departments have dollars

to spend on discovering what things are most shared. The field of education in

interested to know how best to cultivate young minds. The military wants to

know how to brainwash and manipulate through propaganda - and so on and so forth.

The early, narrow focus within academia on the topic of meme-gene co-evolution has had a large

negative impact on the field of Darwinian cultural evolution that continues to this day. Looking

at the modern literature on the topic the obsession is less intense than it once was, but still

a significant factor. I wish the whole field would shake off its obsession with ancient history,

and get more involved in the modern world.

We need a healthy theory of cultural evolution partly to help us guide the course of

cultural evolution on the challenging oceans represented by the modern technological

world. The obsession with human DNA evolution isn't helping too much with this.

Culture is now moving so fast, that meme-gene co-evolution is rapidly becoming an

irrelevant topic. The academic experts in the field need to get off their old

bandwagon and get with the program.

Susan Blackmore Susan Blackmore has many good memes - as well as a few more dubious ones. In her recent description

of her experience lecturing on memes in Oxford (recounted in A hundred walked out of my lecture), there was one of the more dubious ones. Susan said this:

I persevered, trying to put over the idea that evolution is inevitable – if you have information that is copied with variation and selection then you must get (as Dan Dennett p50 puts it) ‘Design out of chaos without the aid of mind’. It is this inevitability that I find so delightful – the evolutionary algorithm just must produce design, and once you understand that you have no need to believe or not believe in evolution.

She presented the same idea at TED. The problem with the idea is devolution. In a nutshell, whether evolution results in the accumulation or the destruction of design depends a lot on the mutation rate. In a sufficiently hostile and mutation-rich environment, living systems do not undergo cumulative adaptive evolution - instead they exhibit devolution - progressive loss of function, possibly culminating in eventual extinction. It isn't really very accurate to say that "evolutionary algorithm just must produce design". It can also destroy and extinguish all appearance of "design" - and often does so, in hostile environments.

If evolution only created design, living systems would have a rosy future. As it is, they could easily be wiped out by a stray solar mass. Evolution can destroy - as well as create.

Alan Winfield recently claimed (on Twitter):

Memetics claims to resemble bio. evo. but only at the highest level of process: variation, selection and heredity.

I don't think this is true. In memetics, cultural evolution is part of biological evolution - since

culture is part of biology.

Cultural evolution resembles DNA-based evolution in a wide variety of ways. There's adaptation, drift, kin selection,

hitchhiking and linkage. There's parasitism, mutualism, epidemics, stasis, phenotypes, ontogeny and progress. There's Hamilton's

rule, Wright's "shifting balance" theory and Fisher's fundamental theorem.

Of course, there are differences too - but the similarities are widely under-appreciated - and they run deep.

The point of memetics is to study the differences between genetics and its cultural equivalent - the study of cultural heredity. However, the very first step in that project is to appreciate the similarities with genetics - so you can make appropriate use of all the work that has already been performed.

Some bits of memetics entered common usage before the 2011 online meme explosion.

Here are some examples of what we might call "folk memetics":

- Contagion - in the dictionary the term refers to both organic and cultural influences;

- Corporate DNA - this term has its own wikipedia page;

- Organizational DNA - this term seems to have been coined in 1993 - it took off in 1995;

- Man-machine symbiosis - this term dates back to the 1960s;

- Artificial life - this dates back to the 1980s;

- Computer virus / worm - dates back to the 1970s;

- Earworm - Wikipedia says the term dates from the 1980s. It took of in 2009.

- Go viral - this phrase took off in 2009;

- Epidemics - the "obesity epidemic" and the "smoking epidemic" point towards generalized epidemiology;

- Emotional contagion - as illustrated by mass hysteria.

Of course there are also examples of memetics-like thinking dating back to before the 1970s. For example:

Popper's popular phrase: "letting our ideas die in our stead" implies that ideas are alive - a la memetics.

Similarly August Schleicher was viewing languages as organisms back in the 1800s. Here he is in 1863:

Languages are natural organisms, which, without being determinable by the will of man, arose, grew, and developed themselves, in accordance with fixed laws, and then again grow old and die out; to them, too, belongs that succession of phenomena which is wont to be termed 'life'.

The memetics timeline offers an early history of memetics which offers more examples.

How is kin selection compatible with phenomena such as sibling rivalry and fratricide?

A big part of the answer given by scientists is local competition. By virtue of being born near to one another family members often come into competition with one another over resources - and then things can get nasty. Local competition can sometimes counteract and overcome the cooperative force associated with kin selection.

One way of avoiding local competition is to disperse offspring widely. However, this solution involves distribution costs and conflicts with trickle-feeding of offspring.

Cultural local competition is a phenomenon too. Shops face much the same dilemma that organisms do. If a shop creates a descendant shop nearby, that might make it easier to set it up the second shop. Close proximity makes it easier to share employees, stock, resources and training. However the stores might go on to compete with each other for customers. If there are multiple descendant shops, a failure to disperse them widely can also mean that the descendant shops compete with each other.

A form of kin competition is often observed acting between related products from the same company. On one hand, companies want to produce a diverse range of products - to expand and saturate the niche represented by their market. However, their products are similar and often compete with each other. This situation can be modeled by treating the products as sterile workers, and then applying the theories associated with kin selection and kin competition.

A similar effect can be found in academia. For example, where memes inside one professor might be reluctant to propagate themselves into another similar professor in the same department - or both professors will soon be expending their resources in fighting over the same grant money - a fight which can be simply avoided if meme reproduction is delayed until after the grant is awarded.

If there are multiple offspring organizations, they often compete with one another for resources from the parent organization(s). This is an example of the cultural version of sibling rivalry.

Offspring organizations and parent organization often share both memes and genes. Genes through things like nepotistic job offers and domesticated plants and animals - and memes through "organizational DNA" - a piece of "folk memetics" terminology. However, for most types of companies and organizations, shared memes will be a more potent force than shared genes. Cooperation between parents and offspring will be down to cultural kin selection and reciprocity - while the extent to which they compete for resources will erode that cooperation.

As is seen in the organic realm, cultural kin competition promotes dispersal. There are fewer conflicts over resources if offspring are widely separated in space.

Said Simon

Said Simon posted an article trashing memetics yesterday - titled: " Memes and Cultural Evolution". Here is my reply:

Memes are like genes - in that both transmit heritable information down the generations.

Complaining that memes split culture into little pieces is rather like complaining that bytes split computer programs into little pieces. Computer programs are full of inter-dependent components, but that doesn't mean that you can't split them into pieces. You can. It's the same with the heritable component of culture. Or anything which is composed of information. This is a property of Shannon information in information theory - and has nothing specifically to do with culture.

Genes interact during the process of their expression too. Their interactions are very complex. I sometimes wonder whether those who complain that memes divide culture into pieces have any knowledge about how genes divide organisms into pieces - and how complex ontogeny is. To me, these organic processes also look highly complex.

You can build models of meme dynamics that assume their interactions are linear - just as you can build models of genes that assume their interactions are linear - but these models should not be seen as limiting the entire domain - they don't limit the scope or applicability of the underlying concepts.

Few complain that "gene" is not useful term because genetics fails to capture the complexities of ontogeny. We have developmental biology which looks at that complexity. In many ways, the point of genetics is to ignore and bypass that complexity, and concentrate on recombination, mutation, and so on. It is the same with memetics.

Critics would be welcome to discuss the wisdom of applying the existing distinction between genetics and developmental biology to cultural evolution. However they should first understand the proposal. Complaining that genetics seems to ignore developmental processes won't cut it. That is the point of genetics - it specializes in another subject area. That's not to say that developmental processes are unimportant or unrelated - just that they are not the proper subject area studied by the genetics department.

Critics can keep harping on about how memetics ignores the complexities of cultural development - but I don't think they are doing themselves any favours. From the perspective of memetics, they are just wasting their breath and failing to usefully contribute. We know about cultural developmental processes. Yes it is complex = but it is a different subject area. Memetics studies the recipies and the mechanics of how they change. How recipes make cakes is a related subject - but humans are forced to specialize by their limited brains; so academic topics have to be subdivided - and this seems like a highly-appropriate fault line with a proven history in mainstream biology.

Memes are not ‘practices’, ‘approaches’, or ‘traditions’ - any more than genes are cells, limbs or proteins. The point of the idea is to distinguish between heritable information and its expression. Between cultural genotype and cultural phenotype. "Cells", "limbs" and "proteins" are important concepts - but they aren't genes, and they can't be used to replace the concept of "gene".

To recap, the virtue of distinguishing between heritable information and its expression, is that the heritable information is the only thing that lasts in evolution. Everything else is not passed on, not inherited. For many kinds of analysis, it can be ignored. If you look at evolutionary biology you will see the utility of this approach.

The complaint that memetics is reductionistic has some truth to it. It does, after all involve splitting a phenomenon into pieces and analysing the pieces - and the interactions between them. However, reductionism is bedrock of the scientific method. It is the main way that science understands complex phenomena. Reductionism is a very important tool in the scientific arsenal. If you don't use it you will lose useful knowledge. Essentially, if you think 'reductionism' is a bad thing, you need science 101.

Contrary to your claim, using the term "meme" is not a form of intellectual "laziness". Memes are mostly just terminology for cultural evolution. Practically every theory of cultural evolution that has been proposed has some term for heritable cultural information. Boyd and Richerson used "cultural variant". Lumsden and Wilson used "culturegens", Donald Campbell used "mnemones". Carl Swanson used "sociogenes" - and so on and so forth with dozens of meme synonyms. "Meme" is just the term that won the competition between these numerous competing terms.

It is the best term, I think. It is short, and it is reminiscent of "gene" in evolutionary biology. It also lends itself to conjugation - as in "memetic engineering", "memetic algorithms", "population memetics", "meme pool", "memetic hitchhiking", etc. I can think of no better way to gently remind people of the under-appreciated truths that culture plays by Darwinian rules, is subject to natural selection, and is part of biology. No wonder it trounced its competition.

Over 150 years after Darwin, memes and cultural evolution are finally filtering through into mainstream consciousness. There's an explosion of activity in the area. With scientific growth comes scientific conflict - and on the edges of science tempers can fray, misunderstandings can arise - and there can be territory disputes. However, it would be helpful if the practice of "steelmanning" became more widespread. Creating straw man caricatures of opponent positions and trashing them might be fun - but is not all that productive. Progress in science needs critics that attempt to understand the positions of their opponents before trashing them.

Anthropologists have long studied cultural kinship. As I put it in my cultural kin selection article:

Anthropologists had previously distinguished between "biological kinship" and "social kinship" (Hawkes, 1983) or between "natural kin" and "nurtural kin" (Watson, 1983) - but they mostly lacked a coherent theory about the evolutionary basis of these categories. Cultural kin selection helps to explain why these traditional anthropological categories are as useful as they are.

However, anthropologists essentially failed to discover cultural kin selection. This was probably largely because of their widespread rejection of cultural evolution - apparently due to fears about eugenics and the like. Scientifically speaking, this was an even bigger mistake.

As a result, attitudes towards cultural kinship within anthropology went in other directions. Anthropologists often seem to see "social kinship" as one of the key reasons for not applying Darwinism to humans. By contrast, in memetics, cultural kin selection is one of the centre pieces of applying Darwinian evolutionary theory to humans. To illustrate the anthropological perspective, here is a quote from Dwight Read's The Evolution of Cultural Kinship: A Non-Darwinian Odyssey:

I take up the question of whether or not the evolution of human societies and cultural systems from a non-human primate ancestor can be accommodated within a Darwinian framework for evolution. I assume that for a non-human primate species, its social structure, form of social organization and kinds of social behavior evolved through Darwinian processes such as biological kin selection, inclusive fitness, reciprocal altruism between biological kin, and so on, including direct phenotypic transmittal of behavioral traits viewed as part of the phenotype of an individual organism. The fundamental question being addressed, then, is whether or not we can embed the evolution of human social and cultural systems within this framework and the conclusion I reach is that the evolution of human social and cultural systems cannot be adequately embedded within this biological framework for the evolution of social systems.

It seems evident that one side of this debate is sorely mistaken. In general, it appears that most of the anthropologists involved are not properly aware of cultural evolution - and their reasoning about Darwinism falls apart at that point. An understanding of memes changes everything.

One famous discussion of genes recognizing themselves in other individuals who are not necessarily close relatives involves the "green beard effect" - an idea which was christened by Richard Dawkins. He imagined a gene for growing a green beard and another gene that caused altruism to those with green beards - and hypothesized that the combination of these genes might cause a green bearded group of altruists to spread in a population. He then raised the issue of what would stop cheats from displaying the green beard and accepting the resulting altruism, but then failing to be altruistic in return.

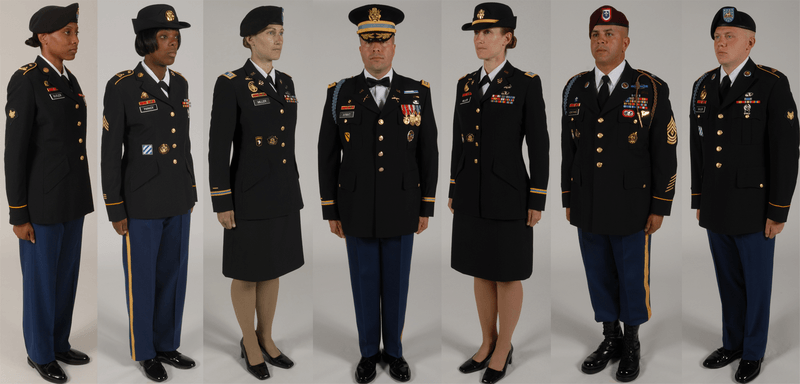

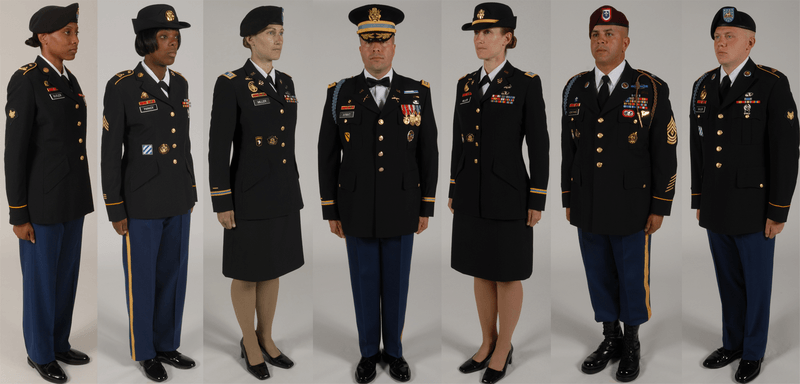

In the case of cultural evolution, such "free riders" can often be identified and penalized. A green beard is a form of signalling. Here we will consider a uniform to be a similar form of cultural signalling. If you put on a nurse's uniform and visit a hospital you will probably be found out - if you engage in very many interactions with other staff members. Much the same would happen with an imitation police man in a police station or a fake soldier in the army. The uniform is only one of a large number of cultural traits marking out genuine members of these "tribes" - and it is difficult for an invader to fake all of the required markers. Some tribes develop marks of group membership that are even harder to forge - with piercings, tattoos, bizarre haircuts as well as distinctive clothing, habits and dialects. So: in the cultural realm, cheaters tend to get found out and punished - and that is one way in which the effect can be made to work.

The ideas in the field of tag-based cooperation are a little bit like those associated with the "green beard" effect. Studies of tag-based cooperation have shown that green beards can be less vulnerable to exploitation than was originally thought. For one thing, when a tag or marker is successfully exploited, another tag can be adopted. Also, the whole idea of having genes for altruism towards those with the 'green beards' had always seemed a little bit contrived. Fortunately, this turns out not to be necessary. In cultural evolution, organisms can simply learn which tags best signal altruism in their environment - and preferentially adopt them.

Cultural "tags" or "tribal markers" probably play a number of roles. Knowing who is in your tribe facilitates reciprocal altruism. It indicates who can be punished for defections against group members - and who future interactions can be expected with. Tags also facilitate cooperation based on cultural kin selection. If memes are able to credibly signal their presence in humans, related memes may be able to use the perceptions of their hosts to identify copies of themselves in other people, allowing them to manipulate their hosts to act so as to favour copies of themselves in other bodies. Even without such behavioural manipulation, tags can still facilitate altruism - by allowing groups of cooperators to form and help each other.

The green beard effect has sometimes been used as an alternative explanation to kin selection. Mark Pagel uses the "green beard" terminology - instead of talking about cultural kin selection - in his book Wired for Culture. However it is important to remember that the green beard effect is a type of kin selection. Green beards indicate shared ancestry - and that is still true regardless of whether they are transmitted via DNA genes or culturally. In one case, genetic ancestry is involved. In the other case it is memetic ancestry.

One of the reasons why kin selection makes useful predictions is that it depends on a long history of interactions with kin, allowing the evolutionary process to 'learn' about the significance of these relationships. However, in cultural evolution, engineering could be used to produce more-or-less any behaviour towards kin that the engineer likes - reducing the predictive value of the coefficients of relationship used in kin selection theory. This is potentially a significant issue for those studying cultural evolution - since many memes are, at least partially memetically engineered.

An alternative view of (say) military uniforms is that they are the products of memetic engineering by generals who want to manipulate their troops into higher levels of cooperation with each other by exploiting the association between perceived kinship and cooperation. This then benefits the generals - and probably their genes. This sort of picture sounds plausible - and makes no mention of cultural kin selection. The explanation that military uniforms are memetically engineered by generals apparently fits the facts without invoking cultural kin selection.

The first thing to note is that military uniforms are actually an ancient phenomenon with a long evolutionary history - and so there's considerable scope for evolutionary and selective forces to act. The other main point is that explanations in terms of benefits to humans and benefits to memes should not necessarily be seen as being alternatives to each other. If you have gene-meme coevolution, often there is evolution towards mutualism - in which both genes and memes evolve to avoid being damaged by the other party. Occam's razor suggests that when two explanations of a phenomena are offered, often only one of them is true. However, in cases of gene-meme coevolution the explanations that "genes benefit" and "memes benefit" are often both true - because of the phenomenon of evolution towards mutualism.

Memetic engineers could engineer whatever memes they like. However, it is often easier to reuse memes that are already available. Also, engineers typically want the memes they engineer to spread. In those cases, making memes that can help copies of themselves in other bodies is one way of doing that - so memetic engineers can be expected to engineer kin recognition and kin-based cooperation into their products - in much the same way that natural selection often does. Having an intelligent designer involved doesn't usually change what forms are adaptive, but it does allow adaptations to arise more quickly. Intelligent designers could fight against natural selection - by engineering forms that are maladaptive. However, only rarely are they motivated to do so. It is quite common for them to want their products to be popular and successful.

It is no accident that the uniforms of military, sports teams, religious orders, hospital workers and so on use culture to make their wearers resemble kin. The producer of this adaptation could be an intelligent agent, it could be evolution via natural selection - or it could be a combination of the two. Memetic engineering is only superficially a rival explanation to cultural kin selection. It is better to see memetic engineering as a rival to the hypothesis of "unintelligent design" - of natural selection without minds. Cultural kin selection can still be applied in either case.

Kin selection is an important and central part of the theory of evolution via natural selection. In turn, cultural kin selection is important and central part of cultural evolution.

Kin selection was originally discovered in the 1960s. It contributed significantly to to an enormous revolution in our understanding of evolutionary biology - the gene revolution.

The discovery of kin selection and intra-genomic conflict destroyed the idea that organisms acted as harmonious wholes. Instead, it became clear that organisms were uneasy alliances between factions with overlapping - but different - interests.

As in the organic realm, cultural kin selection is invading territory that was previously occupied by inadequate group selection theories. Today, group selection enthusiasm still rampant in the social sciences. In the organic realm, the switch from group selection to kin selection was a large paradigm shift. Kin selection wound up almost totally eclipsing group selection. Quantitative measurements of relatedness replaced fuzzy and often-inaccurate just-so stories about how some groups reproduced faster than other ones. In the organic realm this was a large displacement of poor quality science with better ideas that were more easily subject to quantification and testing. Group selection isn't exactly wrong - but kin selection carves nature at the joints - while group selection is more like chalk scraping on a blackboard. Regarding family members as promoting each others interests due to shared genes makes a lot of sense. Viewing families as consisting of partially-overlapping groups does not - because the "groups" involved are little more than mathematical abstractions. Kin selection was so obviously superior to group selection that the latter was relegated to the gutter as a tool for understanding the evolution of cooperation.

Cultural kin selection seems likely to result in a big boost to the meme's eye view. In the organic realm, the gene's eye view was often used to help visualize how kin selection worked. Similarly, in cultural evolution, it is often helpful to descend to the level of the meme to fully understand the dynamics of how cultural kin selection works.

Cultural kin selection helps to explain social cooperation. Understanding cooperation is important - partly because conflict can be so destructive. Cultural kin selection helps to explain our economic system, copyright law, our education system and how our military forces operate. It helps to explain why humans congregate in the groups that they do. As in the organic realm, cultural kin selection is tremendously important to a proper scientific understanding of the world.

Hamilton published on kin selection in 1964. Since it is 2014 at the time of writing, that was 50 years ago. This gives some indication of the scale of cultural evolution's scientific lag.

Many parasites face different selection pressures within individual hosts to the ones they face when migrating between hosts. Within hosts, parasites evolve and compete for resources - with the most virulent strains coming to dominate. However, this may be a poor strategy for spreading between hosts. If a parasite steals host resources to the point where the host becomes bed ridden, the chances for infecting other hosts via social contact may go down. Steven Frank once explained these dynamics as follows:

A long period of within-host evolution, with many rounds of parasite competition and selection, may favor the origin and spread of increasing competitiveness between parasites, leading to greater virulence. That evolution of increasing virulence occurs during the time of an infection within a single host. Such evolutionary increase of virulence can kill the host and, in consequence, kill the parasites themselves. In that regard, the newly evolved virulence is short-sighted, because it provides a local advantage to the parasites in the short run but leads to their extinction in the long run.

Cooperation between parasites within hosts can be explained as a type of kin selection - since the parasites involved are typically all close relatives.

Intriguingly, memes may exhibit similar effects - as part of cultural kin selection. Memes are commonly copied within brains. They undergo selection within brains and compete for space, attention and other resources. However, the selection pressures that act on memes within brains may be different from the selection pressures that apply to memes that move between brains. Because copies of memes that descend from a common ancestor within an human are kin, they are more likely to cooperate with each other while they are together inside the same organism - in order to maximise their transmission rates between hosts.

One point of uncertainty concerning this idea is the extent to which memes are copied within brains. Most of our knowledge of meme dynamics comes from studying them as they move between brains. Less is known about what happens within brains - partly due to the primitive state of the associated neuroscience and brain scanning technologies. It is not necessarily obvious that memes are copied much within brains - since the brain could be doing something like copying pointers to memes - or deriving new memes from existing ones (to borrow some metaphors from computer science).

However, some cases of meme copying within the brain are fairly clear. Long-term memory is one likely candidate. Copying seems likely to help explain long-term memory's fidelity in the face of entropic forces. An occasional cycle through short term memory may be involved in the refresh in some cases. Also, some of the low level mechanisms supporting long-term memory appear to involve copying.

Another case involves short term memory. Many people talk to themselves - in a process which acts like a short circuit in the process of talking out loud and hearing what is said. They also do things like repeat phone numbers to themselves - to help them remember the digits by keeping them active in short-term memory. Here, it is pretty obvious that copies are being made. When you have a song in your head (an earworm) something similar is usually happening.

The dynamic behaviour of meme copying within hosts is illuminated by certain mental illnesses in which things break down. Schizophrenia, paranoia, depression, OCDs and other mental illnesses appear to involve massive internal over growths of memes. These memes constantly occupy short term memory, use it to make copies of themselves, resulting in unhealthy obsessions. If the meme is "I am worthless" the patient becomes depressed, while too many copies of the "they are out to get me" meme tends to result in paranoia. Mental illnesses are "natural experiments", which scientists can make use of to gain understanding in areas where it would be unethical to perform experimental interventions. An excellent book on this topic is Genes, Memes, Culture, and Mental Illness: Toward an Integrative Model by Hoyle Leigh.

In the organic realm, parasites may sacrifice themselves for close relatives in the same host. In particular some mind-control parasites enter the brains of their hosts in a sacrificial move that leads to their own destruction, but the propagation of their kin. This happens with Cordyceps fungus in ants, for example. In extreme cases, memes can do much the same thing. Suicide bombing memes and patriotism memes are not averse to sacrificing their hosts so that their relatives can flourish. Disturbingly, in such cases, meme overgrowths similar to those that occur in mental illnesses are appear to be part of the normal reproductive strategy.

For those concerned about mental health issues, meme overgrowths within minds can be counteracted by a healthy memetic immune system.

This article is based on an excerpt from my forthcoming "Memes" book.

Eusociality

Eusociality is a type of social organisation used by ants and bees - in which many individuals form a highly cooperative group and reproductive capabilities are suppressed in most individuals. Multicellular organisms originally formed out of eusocial groups of cells that clumped together for the advantages that group living brought to them.

Eusociality is common. If you count multicellularity as an advanced form of eusociality, then it is found everywhere. Even if you only consider cases where the individuals still have some kind of semi-independent existence, the prevalence of ants and bees in the biosphere means that eusociality is still a very important phenomenon.

Though meme-infested humans do exhibit ultrasociality, we are not yet near to eusociality - since we don't exhibit reproductive suppression. While it's possible to imagine a future populated by sterile clones of celebrities - and other in-demand individuals - we aren't there yet.

Eusociality is one of nature's ways of building cooperative systems. If offspring can reproduce independently, but travel slowly they often compete with their parents and their siblings as they are forced to compete with them for resources. A eusocial colony is a simple way of building cooperative systems on a large scale.

The widespread occurance of eusociality in the organic realm, raises the issue of what its status is in the cultural realm. It turns out that eusociality is common there too. There are many cases where reproductive 'queens' and sterile 'workers' can be identified in cultural evolution. Books are manufactured in factories - where most of the copies are made - and most of the copies will be destroyed before they manage to reproduce. However the existence of the copies acts to channel resources back towards the reproductive individual - enabling them to gain power and produce more copies - for example by book sales funding marketing and advertising.

Cultural eusociality

Eusociality is an extreme case altruism based on kin selection - in which workers give up their own opportunities to reproduce to help their queen to reproduce. It is also widely seen in the realm of human culture. There are many cases where the equivalent of cultural "queens" send out cultural "workers" out into the world to channel resources back towards the queens. This pattern is seen with consumer electronics, recipes, factories, server-side software, digital rights management, computer games - and many other phenomena. Cultural kin selection is involved in the explanation for these kind of phenomena.

To give a specific example, the use of patriotism to cause soldiers to sacrifice themselves in battle is an example of sterile workers sacrificing themselves for other reproductive individuals. However, dying in battle is highly likely to be bad for your own genes - so why do soldiers do it? What the deaths of soldiers are adaptive for is the patriotism memeplex. That exists in the form of other copies which directly benefit as a result of the sacrifices of the soldiers. The instance of the patriotism memeplex in the soldiers dies along with its human host - but copies of that memeplex in the generals and politicians survive - and so nationalism spreads. The soldiers are infected by memeoids – their brains are infested with necrotrophic memes which were memetically engineered by the state.

Offspring sterility

In the case of books, their non-digitized form makes copying them challenging. In many other cases, specific sterility features can also be identified. Patents, trademarks, digital rights management - all are oriented towards preventing unauthorised copying of sterile workers - with the aim of increasing the resources that are channeled back towards the original source.

It is usually easy to copy cultural information - so, in cases where reproductive memes are surrounded by sterile workers require special explanation. Several factors can result in offspring sterility - including: - Obfuscation - this protects consumer electronics and microprocessors.

- Cryptography - This involves using technical defenses to make copying difficult - resulting in Digital Rights Management;

- Legal threats - Some types of copying are prohibited by copyright, patent and trademark law;

- Watermarks - This helps to protect some videos, images and money;

- Registration - Some software ensures that it is not copied by "phoning home" - contacting its manufacturer over the internet;

- Dongles - Dependencies on something that is not easy to copy.

Offspring sterility is one of the hallmarks of cultural eusiciality that distinguishes it from simple situations where there is an individual meme which lots of identical copies happen to have been made.

Cultural cloning

Money illustrates that cultural kin can be identical clones.

Money is an example of cultural eusociality which involves identical clones. Notes and coins are not normally copied from. When they are, the copiers are hunted down and imprisoned. Technical measures are used to prevent copying - such as watermarks, metal strips and very detailed patterns which are hard to scan. Notes and coins are usually produced from reproductive individuals inside the treasury. The money in circulation plays the role of workers, the machines in the treasury that produce them are the queens, and the the blueprints for those machines are their heritable material. Money illustrates that the kin involved can be identical clones - as they are in conventional multicellular organisms. Identical clones usually offer the best possible chance of kin selection resulting in mutual cooperation.

Parental manipulation

The mechanism responsible for eusociality is typically the same in the organic and cultural realms. Kin selection acts in both realms - the sterile workers and their queens are closely related. In both cases parental manipulation is often involved. The queens make the workers sterile by building them without reproductive parts, so that they can better help their maker without getting distracted.

Eusociality - or extended phenotype?

When considering cultural eusociality, one issue is whether the sterile forms are better viewed as individuals in their own right - or the extended phenotype of the reproductives. For example, a cake factory makes "sterile" cakes - which are rarely copied from directly. It might be unorthodox to describe those as "sterile workers" - since they don't really contain the same "heritable material" as is found in the cake factory. The process of baking makes "reverse-engineering" the cake challenging - and the cake might better be regarded as the extended phenotype of the cake factory. I call this the "hair and nails` issue because, while human somatic cells are a lot like sterile workers, hair and fingernail tissues are not.

Prevalence

Cultural eusociality is ubiquitous. The printing press produced some of the first mass-produced identical copies of memes. These days, digital copying has reduced the cost of copying further - and some web pages and videos have been reproduced billions of times. In many cases, these highly-copied digital systems exhibit offspring sterility, one of the hallmarks of eusociality. This is often implemented via "Digital Rights Management" (DRM) systems.

This article is based on an excerpt from my forthcoming "Memes" book.

A major breakthrough in evolutionary biology in the 1960s took the form of the development of a theory that could account for much cooperative behaviour in nature. That theory takes on new significance and importance when applied to cultural variation. In particular, nepotism, kinship, relatedness and kin selection all have direct parallels in cultural evolution.

Kin selection

Genetically related individuals frequently cooperate and behave altruistically towards one another. This phenomenon is modeled by a branch of evolutionary theory known as "kin selection". This models cases where organisms engage in behaviour that favours relatives over non-relatives. Kin selection explains parental care, nepotism, eusociality among the social insects, problematical adopted children - and many other phenomena. The original explanation of kin selection invoked shared genes. J. B. S. Haldane was one of the first evolutionary biologists to understand the idea in the 1950s. It was subsequently studied and modeled by William Hamilton in the 1960s. Hamilton said:

The existence of altruism in nature can be explained by thinking about the replication of genes. We need to descend to the level of the gene, rather than the individual, in order to see that the gene exists surrounded by copies of identical genes that exist in all its relatives - in particular in its close relatives, its siblings, who have a half chance of carrying a copy of that particular gene, its offspring, which also have a half chance, parents: a half-chance, cousins: one eighth, etc. Seeing this swarm of genes that exists around a particular one, we can then ask what is the behavior caused by this gene that is most likely to cause the propagation of this set of copies in the relatives around it.

A broadly similar argument applies to memes. This raises interesting possibilities for what we will be calling " cultural kin selection".

Cultural kin selection

Just as genetic kin can be expected to cooperate, so it seems reasonable to expect memetic kin to cooperate - on much the same grounds.

Our understanding of altruism needs to be augmented by considering the reproduction of memes. We need to descend to the level of the meme, in order to see that an individual meme is surrounded by copies of itself in the form of the meme's parents, offspring, siblings and cousins - its memetic kin. Seeing this swarm of memes that exists around a particular one, we can then ask which of the behaviors that could be promoted by this meme would be most likely to cause the propagation of the swarm of copies of itself that surround it.

That kin selection can be usefully applied in the cultural realm is an old idea. Boyd and Richerson discussed the idea in 1980. Paul Allison and Francis Heylighen noted it in 1992. Anthropologists had previously distinguished between "biological kinship" and "social kinship" (Hawkes, 1983) or between "natural kin" and "nurtural kin" (Watson, 1983) - but they mostly lacked a coherent theory about the evolutionary basis of these categories. Cultural kin selection helps to explain why these traditional anthropological categories are as useful as they are.

Suicide terrorism represents a good example of cultural kin selection. All the memes in the suicide bombers are extinguished, but copies of their memeplexes in other individuals are promoted by the publicity generated by their actions. Suicide terrorists believe that they are part of a brotherhood and that their actions help their relatives. This is not far from the truth - though the "brotherhood" is a cultural - not an organic one - and the bombing typically promotes associated memes - not organic genes. Cultural kin selection is involved many types of human social behaviour - including political, military, religious and professional groupings.

Parental resource allocation

Parental investments in offspring are one of the the most prominent manifestations of kin selection in the organic realm. These so not require particularly advanced cognition or much in the way of recognition of kin. Parents usually provide their offspring with more than just a genetic inheritance. They often provide them with material resources, to help their offspring get off to a good start in life. Parental investment typically involves one or more of these two types of contribution:

- Resource boluses - allocated at birth;

- Resource trickles - supplied over an extended period of time;

Parents sometimes provide a resource bolus - to help give their offspring a good start in life. For example, this can take the form of albumen in a large egg, or stored fats in a large nut or seed.

Another strategy is to provide a resource trickle over a more extended period of time. This requires an extended association between the parent and their offspring after it is born. Such extended relationships do exist - but they are not that common: many organisms simply abandon their offspring. Trickle feeding is the approach taken by strawberry plants, for example. They reproduce sexually using seeds - but also employ vegetative reproduction - using "runners". In this latter case, the baby strawberry plants are attached to their parents by fibrous stalks that provide them with nutrients while they are getting established. Among mammals, 'brooding' is common and maternal affection for offspring is fairly widespread. Humans also use trickle-feeding techniques with their own offspring. Maintaining a connection between parent and offspring in this way allows parents to dynamically allocate resources between their offspring - depending on their perceived viability.

Cultural parental resource allocation

Resource boluses and resource trickles are both found in cultural evolution. Resource trickles seem to be more common than in the organic realm. The world of finance provides many examples. One example is sales people: it is common to put new recruits on a salary after teaching them how to do their job. This allows them to support themselves while they are learning their new trade - but before they are able to earn a healthy commission. Another example is franchises. When a new franchise starts up, it is sometimes supported economically for a while by existing ones - while the new establishment finds its feet. Offices, factories, farming and mining operations often behave in a similar way.

Maintaining a connection over which funds can be transferred is simple and cheap in the modern world, and a resource trickle provides more dynamic control over the flow of resources. Cultural parents don't normally perish during childbirth - and so parents are often around to supply a resource trickle.

Religious memeplexes are among those that make extensive use of extended parental investments. Religions are often old and highly evolved elements of culture, with considerable adaptation to the human psyche. It is common for them to feature extended indoctrination periods. Sometimes the indoctrination takes place by trusted family members during childhood years - when the human mind is at its most impressionable. There's an extended association between the religious memes in the adult teachers, and their cultural offspring inside the children.

Teaching

A common example of cultural parental investment involves teaching. Teachers sometimes have extended relationships with their students. While they are together, memes are planted in the minds of the student - and the teacher cares for and nurtures them. Teachers don't just deliberately expose people to their memes, they check to make sure they are installed properly, and provide additional exposure if they are not. The memes are repeated and reinforced until they are well established in their new host. If one teaching method fails, another teaching method can be tried. Teachers often act as though they care for the future welfare of the memes they implant in students. They also act as though want the students to keep coming back - so that more memes can be installed. The meme's eye view pictures the memes inside the teacher influencing their behaviour - so that they ensure that the memetic offspring are well established in the minds of the students. If the student is inspired to subsequently go on to teach others, that is better still.

Teachers often teach others to teach. That's a case of memes not just caring about their immediate offspring - but trying to ensure that they become long-term ancestors. Obviously, being linked with memes associated with teaching others is a way for memes to improve their own fitness. Teaching memes are thus in demand - many other memes act as though they want to be associated with them.

Cultural kin recognition

Outside relationships that involve teaching, cultural kin selection acting on memes inside different humans demands that memes somehow "recognize" each other while they are inside other human bodies. For mental symbionts to identify other mental symbionts while they are inside human bodies is a non-trivial feat. If you think of memes as software, that may help to understand how such a thing is possible. How this feat is actually performed is interesting. Memes typically use the same psychological apparatus designed for recognizing relatives in order to to identify copies of themselves inside others.

Memes often subvert their host's kin recognition for their own ends by making non-relatives appear to be relatives. A concrete example of subversion of host kin recognition may be found on the battlefield. Shared military uniforms indicate shared nationality memeplexes. These memeplexes are prepared to sacrifice themselves for copies of themselves in other bodies – and they manipulate their hosts to achieve that end – to fool their hosts into believing that their fellows are their genetic kin – not just their memetic kin. This is why military uniforms are often designed to cover the entire body and make soldiers appear to be identical clones of one another - to act as a superstimulus to the kin recognition apparatus in the human brain. Shakespeare expressed the feeling of brotherhood associated with warfare - writing:

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers; For he to-day that sheds his blood with me shall be my brother.

The human hosts may not literally be fooled into thinking that non-relatives are really kin. However, kin recognition is part of the human psyche - extending down into unconscious realms. While people may not be consciously fooled, part of their brain is still thinking: "kin" - and acting accordingly.

Religions subvert kinship kinship recognition systems as well. Monks are "brothers" in a "brotherhood", and the priests are called "Father". Nuns are "sisters", in a "sisterhood" and the head nun is their "Mother Superior" - or their "Reverend Mother". Then there's the holy "father" - who plays the paternal role. As with the military, the monks and nuns often wear identical uniforms - so they look like kin. Church is all about family - but it the relationships involved are not organic - they are cultural.

Kin recognition has had a rocky ride in mainstream biology in recent years. It has turned out to not be as widespread as was originally imagined. Gardner and West's 2007 article "The Decline and Fall of Genetic Kin Recognition" covers the controversy - suggesting that markers used for kin recognition would tend to rapidly reach fixation - and become useless as kin-specific markers - unless high levels of mutation or selection oppose this. They suggest that selection for marker diversity which is caused by parasites may help to explain why kin recognition is widespread among humans. The theory of gene-meme coevolution suggests another answer to this question - that humans use memes as markers that act as proxies for DNA relatedness that are both highly variable and easily identifiable. In both cases, rapidly evolving symbionts would act to promote altruism by providing a rapidly-changing source markers to act as signals associated with relatedness.

Perhaps the most important thing to say about cultural kin recognition is that it is not a prerequisite for cultural kin selection. David Hales in 1997 claimed that:

memetic kin altruism can only function if memes can induce individuals to distinguish between memetic kin and non-kin.

However, advanced cognition which is capable of recognizing other individuals is not required in order to distinguish kin from non-kin. A strawberry plant doesn't need to "recognise" its own offspring - because it is joined to them by runners. Similarly, many organisms don't disperse their offspring very far from home - in which case, being nice to your neighbours is often much the same as being nice to your relatives.

Memetic relatedness

Relatedness is not always so easy to calculate in the case of culture. Here is Peter Richerson (2010) expressing scepticism on the topic:

In the case of culture, the analog of kinship is very hard to estimate. Having two parents with equal genetic contribution makes the calculation of relatedness easy. In cultural transmission, one, two, a few, or many people in your social network are possible sources of culture. People may use different parts of their network for different cultural domains. No one has proposed a way to estimate cultural relatedness in the face of such problems.

It is not true that no one has proposed a way to estimate cultural relatedness. Paul D. Allison did it in 1992. John Evers did it in 1998. However, it is true that the concept of "memetic relatedness" between people does face some practical problems. We currently have no practical way to sequence all a person's memes - to recover all the cultural information stored in an individual brain. We can, however measure the occurrence of particular memes, via questionnaires and similar methods. In the organic realm, basic a calculation of relatedness on shared genes works quite well - because of the mechanics of meiosis. However, in the cultural realm, memes are not dished out so evenly and uniformly - and one sample of memes might give one estimate of relatedness, while another sample might produce a different estimate. That is a practical problem for estimating memetic relatedness between people - both for scientists and for memes attempting to track their own offspring. However, there are statistical techniques designed to deal with this sort of issue. If you randomly sample some memes from one person and then see if they are present in another person (and repeat the process the other way around) that will probably produce a reasonably usable figure for the memetic relatedness between them. The issue isn't a show-stopping problem.

However, while calculating memetic relatedness between people is not easy, it is often not necessary. Consider for a moment the similar case of kin selection among organic parasites. Some braconid parasitoids attack caterpillas. They crawl into the caterpillar's brain, form cysts, and manipulate its behaviour. These parasites die - but the behavior they induce helps their kin to reproduce. This is an example of kin selection. However, there's no calculation of the additional level of relatedness between the hosts that arises as a result of them sharing parasite genes. Such a calculation would be irrelevant and unnecessary. Kin selection acting on memes is similar. Many of the important relationships are between sets of memes or memeplexes. Calculating relatedness between memes is pretty trivial. Often such relatednesses are either one or zero - i.e. either the memes are either identical copies, or they are not. This idea can be expanded to memeplexes without much difficulty. That is enough to support the theory of kin selection in the cultural domain. Averaging relatedness over all the memes in a single host is often not necessary in order to model the dynamics involved.

Hamilton's rule

The "holy grail" for students of cultural kin selection seems to have been to derive an equivalent of Hamilton's rule. There have been a number of attempts to do this. An early attempt was made in a paper by John Evers (1998) called "A justification of societal altruism according to the memetic application of Hamilton's Rule". This paper derived a variant of Hamilton's rule applied to memes - adapted to deal with horizontal transmission. It was based on the idea of using a figure for the "fraction of shared memes" in place of Hamilton's relatedness. However, John doesn't really go into the difficulties associated with this idea. Also, adjusting Hamilton's rule to deal with horizontal transmission doesn't seem to be particularly urgent to me.

More recently, David Queller (2011) wrote a paper titled "Expanded social fitness and Hamilton's rule for kin, kith, and kind" - which attempted to roll kin selection, "kith" selection and "green beard" effects into an extended version of Hamilton's rule. David Queller's work is not based on memetics. It attempts to cover all kinds of social effect - not just cultural ones. While this work is interesting and general, its generality works against it in some respects. It doesn't allow predictions to be based on shared memes - and that is one of the main virtues of cultural kin selection. David Queller's use of the term "kith selection" clashes with Gordon Rakita's prior use of the term in a potentially confusing manner. I'm inclined to label "kith selection" as unnecessarily-obscure jargon.

Of course, applying an unmodified version of Hamilton's rule directly to pair-wise interactions between cultural creatures is still perfectly possible. In the organic realm, kin selection theory makes use of the idea of "genetic relatedness" - and idea that gives a rough estimate of the proportion of rare genes that are likely to be shared between two individuals. Part of the attraction of Hamilton's rule is that it allows a cheap calculation of this "relatedness" - based on easily accessible information about geneaology. In practice a lot of relatedness figures between cultural creatures are either 0 or 1. The lack of memetic meiosis complicates this approach. Also, in cultural kin selection, there are additional difficulties after relatedness has been calculated. Genes typically affect behaviour in the organic realm fairly directly. However, for the "puppet masters" of memetics, memes must manipulate their hosts in a highly indirect manner. Memes face difficulties associated with accessing host sense data and with controlling host motor outputs. These are broadly similar to the difficulties parasites face in manipulating their hosts. As with parasites, the resulting host behaviour is the result of a battle with host's DNA genes and all the other memes that the host carries. Most memes don't get things their own way. This indirect control over behaviour acts as a further confounding factor which makes it harder for approaches based directly on using Hamilton's rule to produce useful answers.

I think it is best to avoid obsessing over memetic versions of Hamilton's rule. The original Hamilton's rule works in the cultural domain in an unmodified form. The only problem is that the complex and indirect nature of meme expression can mean that it is harder and more complex to apply. Of course, it is still possible to adopt the meme's eye view - and ask how a meme could act so as to affect the propagation of the surrounding swarm of copies of itself. That is still an extremely useful approach - even if you don't directly use Hamilton's rule.

Related content

- Tyler, Tim (2012) Cultural Kin Selection - a teaser.

- Tyler, Tim (2014) Cultural eusociality.

- Tyler, Tim (2014) Technological kin selection.

- Tyler, Tim (2014) The significance of cultural kin selection.

- Tyler, Tim (2014) Cultural kin selection vs cultural group selection.

- Tyler, Tim (2014) Cultural kin selection and the meme revolution.

- Tyler, Tim (2013) A brief history of cultural kin selection.

- Tyler, Tim (2013) Cultural kin selection bibliography.

- Tyler, Tim (2014) Cultural group selection bibliography.

- Tyler, Tim (2014) Homophily.

- Tyler, Tim (2014) Cultural kin selection meets anthropology.

- Tyler, Tim (2013) Tag-Based Cooperation.

- Tyler, Tim (2014) Criticisms of cultural kin selection.

- Tyler, Tim (2014) Cultural kin selection within hosts.

- Tyler, Tim (2014) Cultural kin selection vs memetic engineering.

- Tyler, Tim (2014) Cultural kin selection may have driven imitation capability.

- Tyler, Tim (2014) Links between organic kinship and cultural kinship.

- Tyler, Tim (2014) Misrepresentation of kin selection by group selection advocates.

- Tyler, Tim (2014) Cultural evolution + group selection = a disaster in the making.

- Tyler, Tim (2014) Cultural local competition.

- Tyler, Tim (2014) Cultural superorganisms.

- Tyler, Tim (2015) David Sloane Wilson on cultural kin selection.

- Tyler, Tim (2014) Cultural spite.

This article is based on an excerpt from my forthcoming "Memes" book.

It seems as though writing a book about the science of race differences is a fast track to fame.

In the latest chapter of Nicholas Wade's marketing triumph, a bunch of 139 scientists have recently signed a letter critical of hiss book, saying:

Wade juxtaposes an incomplete and inaccurate account of our research on human genetic differences with speculation that recent natural selection has led to worldwide differences in I.Q. test results, political institutions and economic development. We reject Wade’s implication that our findings substantiate his guesswork. They do not.

As far as I can make out, this declaration is a stupid one. It is, in fact, very likely that recent natural selection has led to worldwide differences in the traits they describe. To describe this as "speculation" and "guesswork" goes contrary to practically everything we know about the extent to which natural selection contributes to variation in observed traits.

So, why would so many scientists publicly put their name to such a daft declaration?

The answer is probably political correctness. As Wade responds:

This letter is driven by politics, not science. I am confident that most of the signatories have not read my book and are responding to a slanted summary devised by the organizers. As no reader of the letter could possibly guess, “A Troublesome Inheritance” argues that opposition to racism should be based on principle, not on the anti-evolutionary myth that there is no biological basis to race. Unfortunately many social scientists have long denied that there is a biological basis to race. This creed, prominent throughout the academic world, increasingly impedes research. Biologists risk damaging their careers if they write explicitly about race.

I've seen some of the negative commentary on Wade's book. A lot of that commentary is tripe. I don't know if Nicholas Wade's book is any good. It seems to be rather DNA-centric. However, Wade does know enough about meme-gene coevolution to argue that cultural variation between groups arises rapidly, creates different selective environments for human DNA genes - which accelerates divergent evolution of human DNA in different areas. This argument is factually correct.

Wade seems to have managed to obtain the substantial publicity he has received mostly by writing a controversial science book on a taboo topic. That this has happened seems to be essentially a good thing. Probably other science writes will pick up on Wade's obvious success - and we'll see more books on "unmentionable" topics. It's hard to avoid the conclusion that this will be a good thing.

Update 2014-08-12: Jerry Coyne in particular comes across as confused about this issue:

The book was about the genetics of ethnic and cultural differences, and while it made a valid point that ethnic groups do show small but significant genetic differences across the globe, there was no evidence for Wade’s main thesis: that differences in behavior among groups, and in the disparate societies they construct, are based on genetic differences. While that might in principle be true, we simply have no evidence for that conclusion, and it was irresponsible of Wade to suggest that such evidence existed.

This is surely an extreme and inaccurate position. Genetic lactose intolerance is one example of genes influencing human behaviour differently in different geographic groups - affecting dairying behaviour.

Of course there are genetically-based behavioural differences between different human groups! I think we have to label those opposing this idea as "race denialists".

For reasonable comments in response to the book, I would recommend Matt Ridley and Larry Moran.

I think that " Universal Darwinism"

is the best term for the expansive Darwinism that extends beyond

biology into realms such as chemistry, physics, geology and astronomy.

For a while I've wondered what we should call... the other kind of Darwinism.

The kind I was taught in school. The kind in most evolution textbooks. The narrow-minded

kind that most scientists today seem to believe in.

In many respects, I think that "Narrow Darwinism" is the most obvious choice.

However, my main concern with this term is that I'm not sure it's

insulting enough. An alternative - which is much more insulting - is

"Blinkered Darwinism". I think the term "blinkered" is about as good at

conveying "narrowness" - and has what is surely the significant virtue of

much more strongly denigrating its associated subject.

The term "Blinkered Darwinism" gets thumbs up from me.

These

are, apparently, words that are never spoken. It's always " you are a social Darwinist",

or " they are social Darwinists" - never " I am a social Darwinist".

For me, that situation is lamentable. "Social" and "Darwinism" are ordinary words with

conventional scientific meanings - their combination should not be a term of abuse.

So: I am a social Darwinist. I think Darwinism is true and am sympathetic to and

supportive of attempts to make society better by applying it to human society.

One of the most obvious approaches to improving society by using Darwinian evolutionary

theory involves

memetic engineering.

This approach has long been advocated by social theorists. B. F. Skinner's 1971 book

"Beyond Freedom and Dignity"

was an early contribution to the topic which illustrates the approach.

Scientists should absolutely not let the term "Social Darwinism" to be dragged into the

gutter by Darwin-haters. "Social Darwinism" is not synonymous with Nazism, and doesn't

entail forced sterilization or gas chambers. That is just a nasty smear campaign.

All kinds of folk did nasty things during the 20th century. However, their crimes

do not - or should not - blacken the doors of their descendants - or intellectual

descendants - forever. Yes, some folk believed in Darwinism and killed or

sterilized some other folk. However many 20th century tribes did similar things -

Christians, Muslims and atheists, for instance, are bigger groups that did far

worse things. That's not to say that doing bad things is OK - if other people did

worse things. It just means you have to get things in perspective.

As far as I know, there's no evidence that Darwin enthusiasts are morally any worse than other folk. The reverse seems much more likely - since an understanding of Darwinian evolution is correlated with educational attainment, which in turn is associated with reduced rates of violence and crime.